Location

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Year of Construction

1896

Architectes et artistes

Pařik Karel (1857-1942), Wittek Alexandar (1852-1894), Iveković Ćiril Metod (1864-1933)

- Contemporary photographies

- History

- Map

- Artistic looks

- Words of people

- Related topics

- Educational activities

History

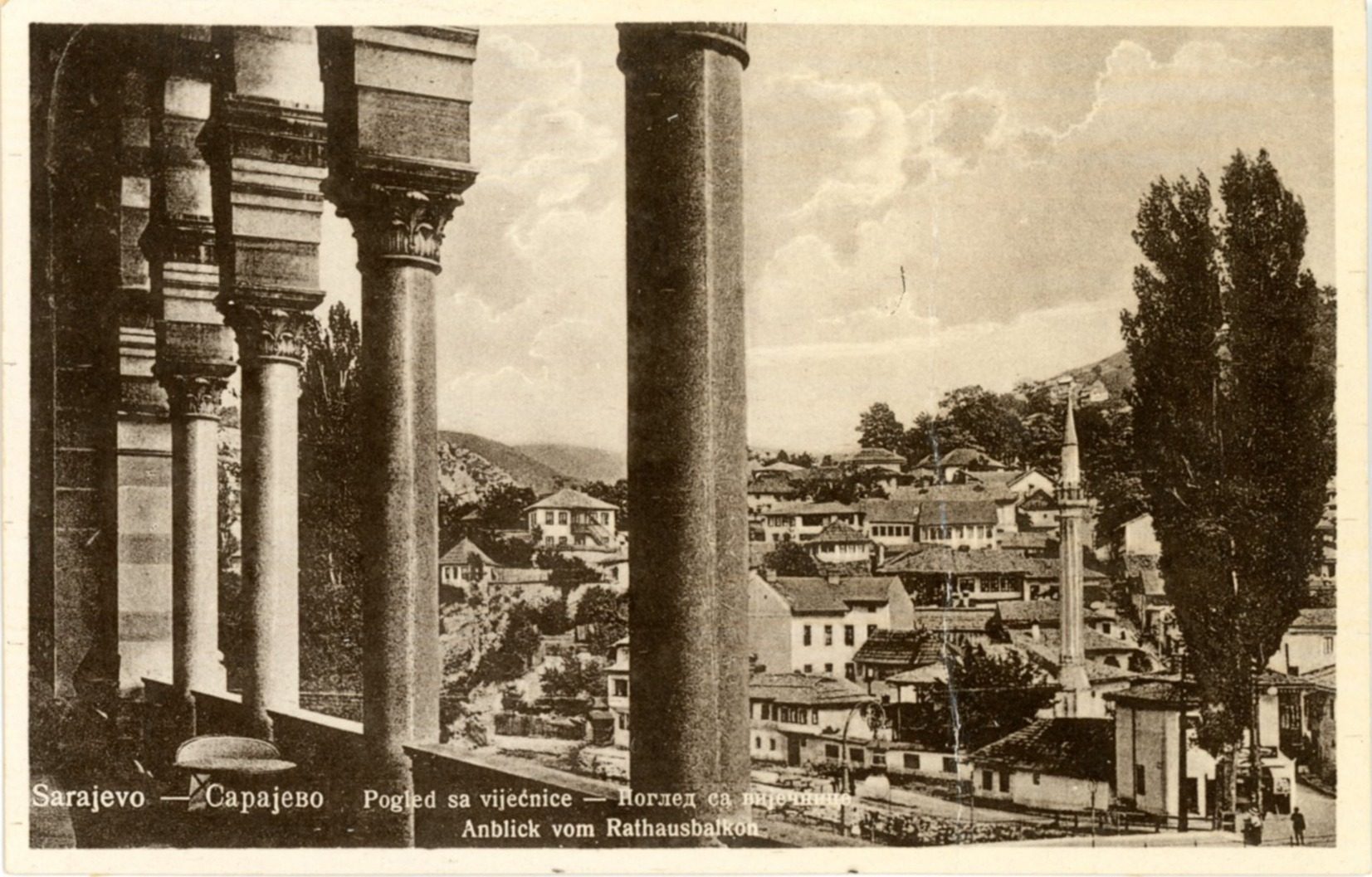

In 1878, the Treaty of Berlin transferred the administration of the formerly Ottoman province of Bosnia-Herzegovina to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The province new rulers decided to build a city hall in Sarajevo to meet the city needs. But although construction planning had begun in the 1880s, the site where building was to be located, on Mustajpaša Square in the heart of Baščaršija, the historical center of the Ottoman city, became official only in late 1890.

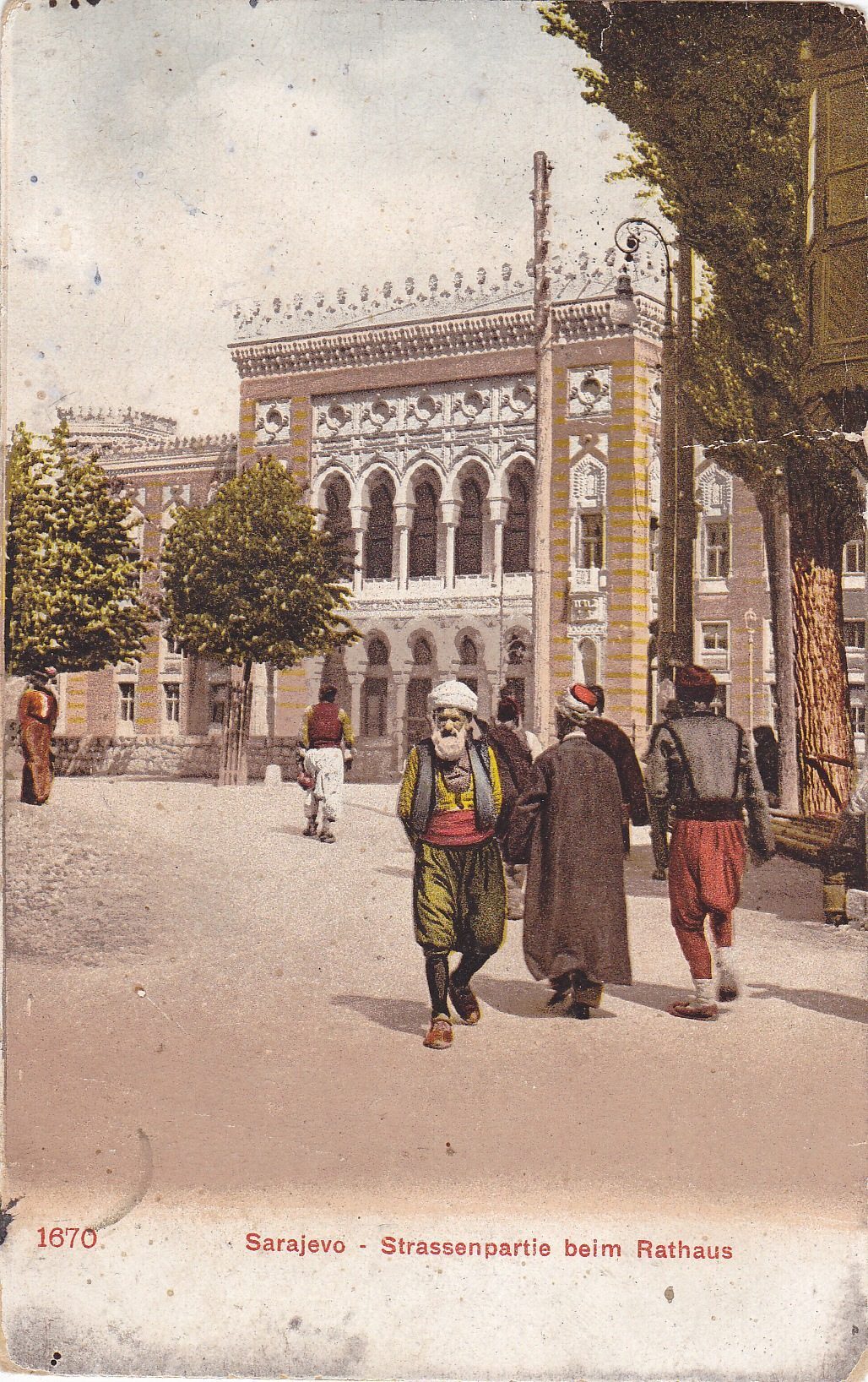

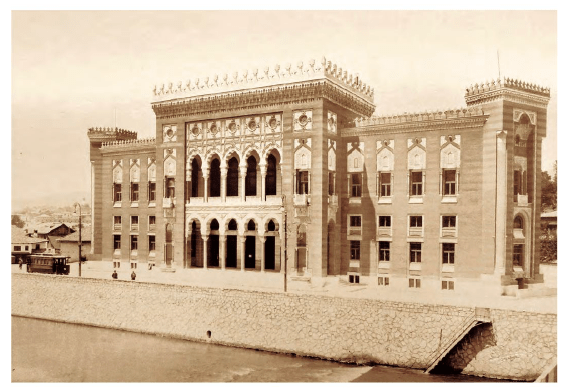

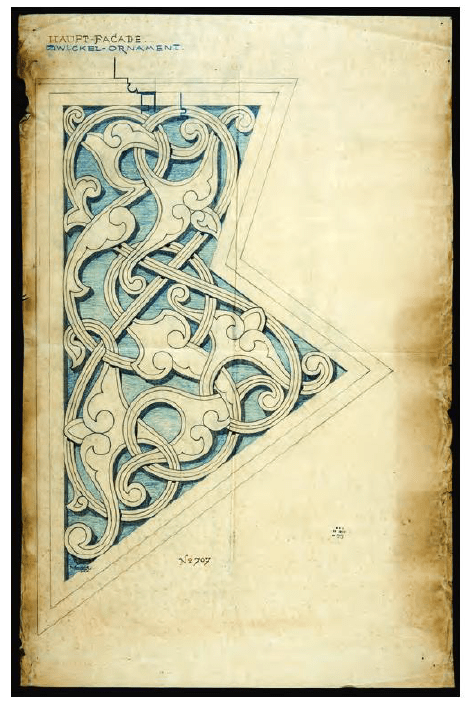

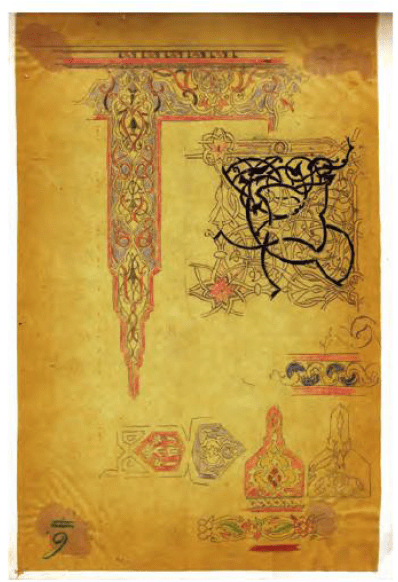

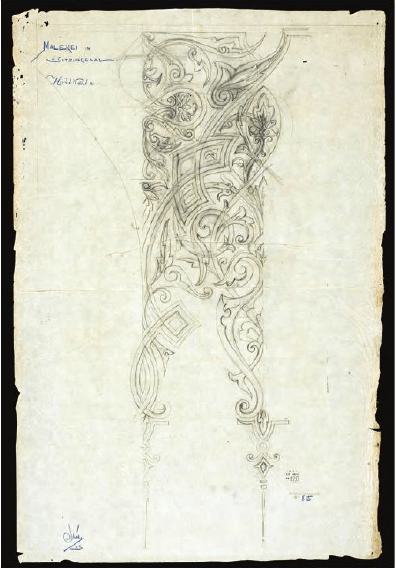

Czech architect Karlo Pařik was commissioned for the project. In 1891, he delivered a preliminary sketch. The building Pařik designed had a floor plan that fit the triangular lot. The Finance Minister of the time, Baron Benjamin Kallay, was disappointed with Pařik’s design, and made his approval contingent on certain changes. Pařik refused to modify the project and withdrew. The project was then handed to Alexandar Wittek, who kept most of the features of Pařik’s design. However, he did acquiesce to Kallay demand that an extra story be added to the building, to make it more monumental, symbolic of the importance of the city hall. Wittek, who had traveled in Egypt, is credited with most of the building’s pseudo-Moorish decoration. Nevertheless, because he died before the construction was completed, all of the working drawings of façades and decorations, dated 1894 and 1895, were signed by a third architect, Ćiril Iveković. Iveković made only minimal changes to the plans for building layout and the façade design. The city hall was finalized, and became the archetype of pseudo-Moorish style in Bosnia-Herzegovina. In fact, Wittek and Iveković also designed the Brčko city hall, erected between 1890 and 1892 in the same style.

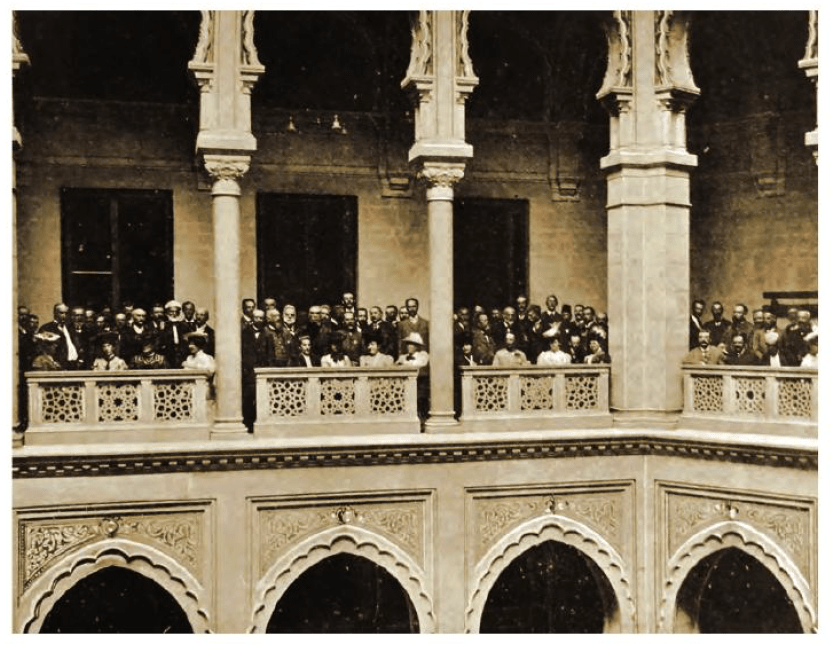

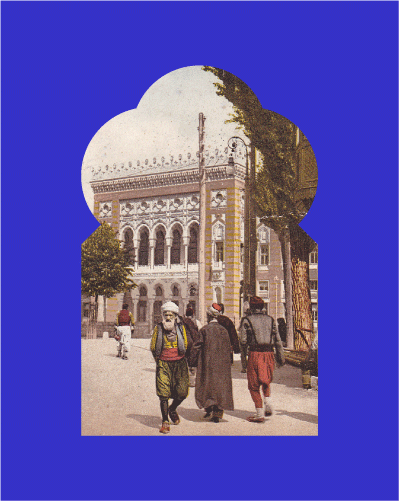

The opening ceremonies were held on April 20, 1896. The triangular building complex is covered by a central dome, and includes a basement, ground floor with mezzanine level, and two stories. Its three corners are graced with prismatic towers and the central sections of the three facades form avant-corps. The main avant-corps, to the south, juts out farthest. Its roof is lined with a frieze and crenellated. Broad stone steps lead to a large gallery porch with five horseshoe arches. The floor above features a loggia.

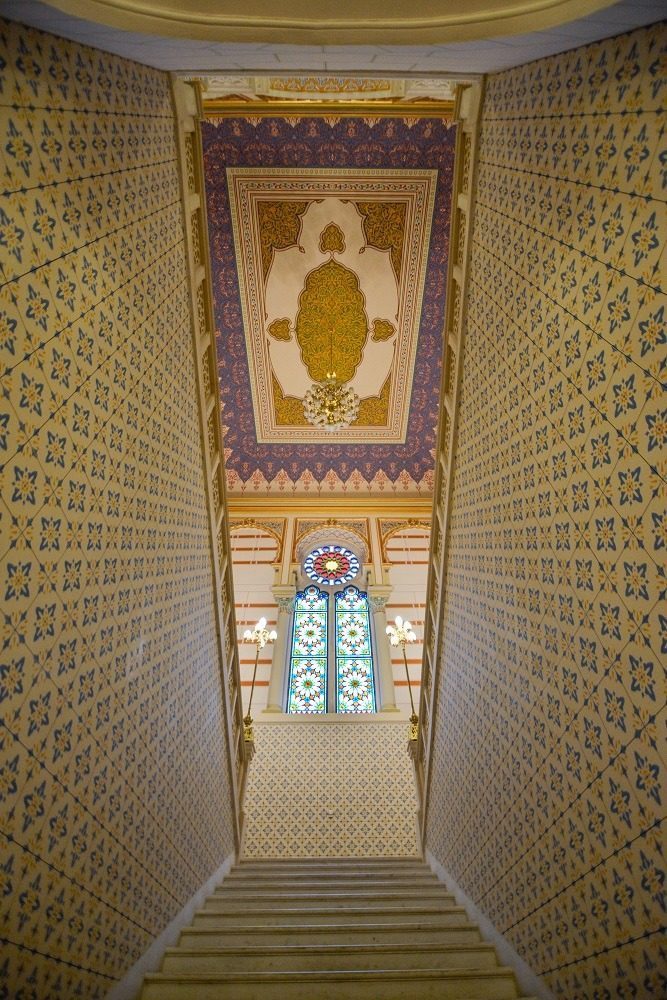

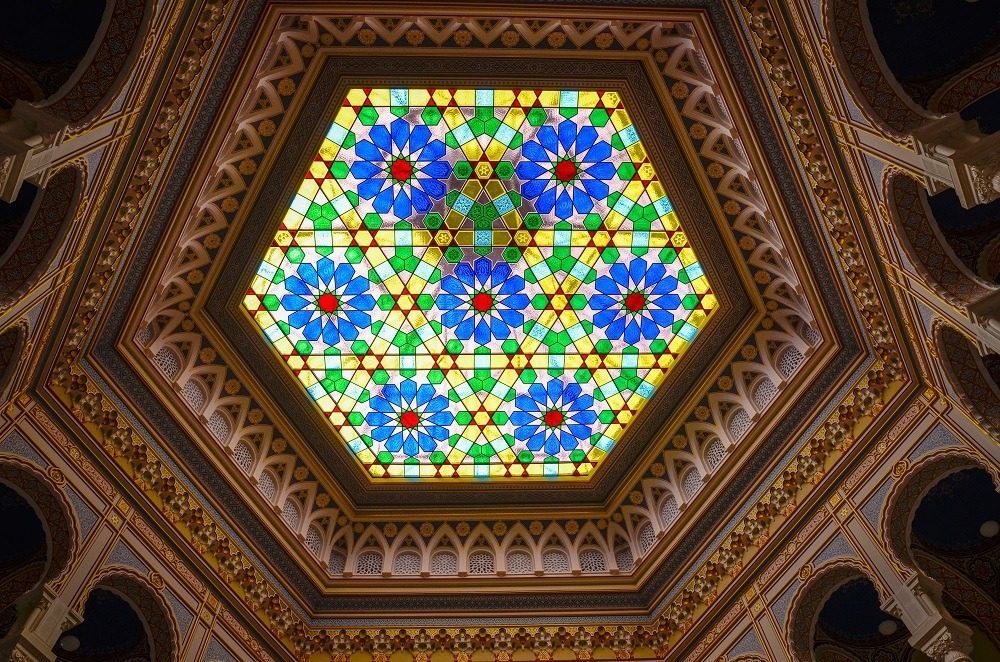

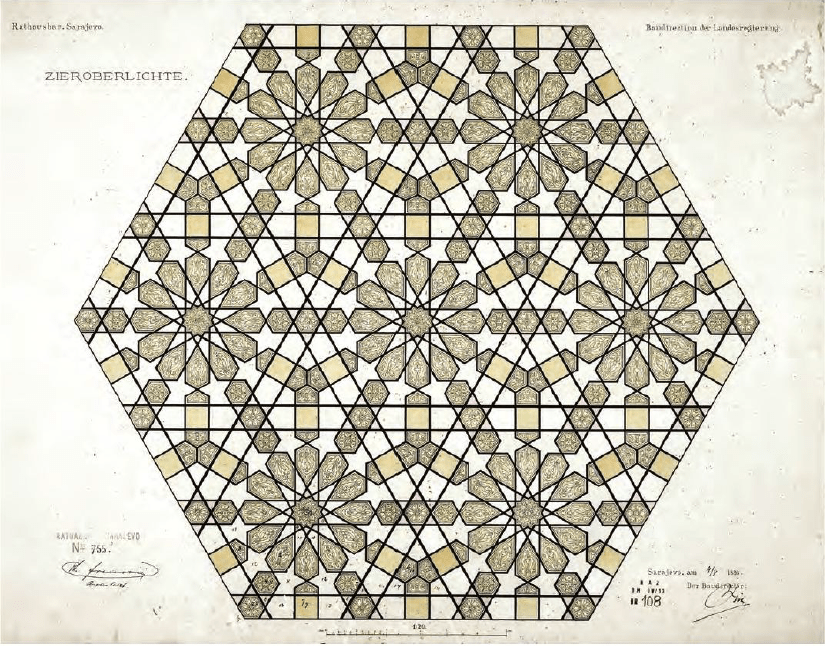

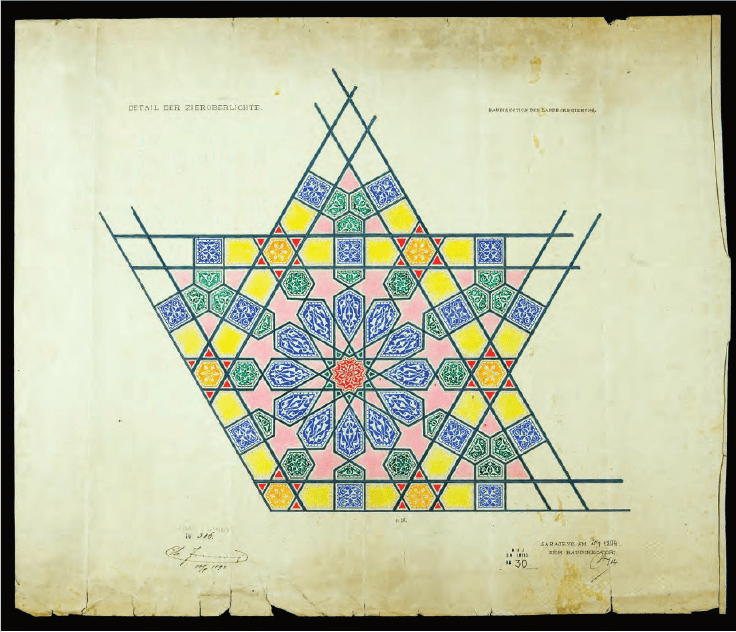

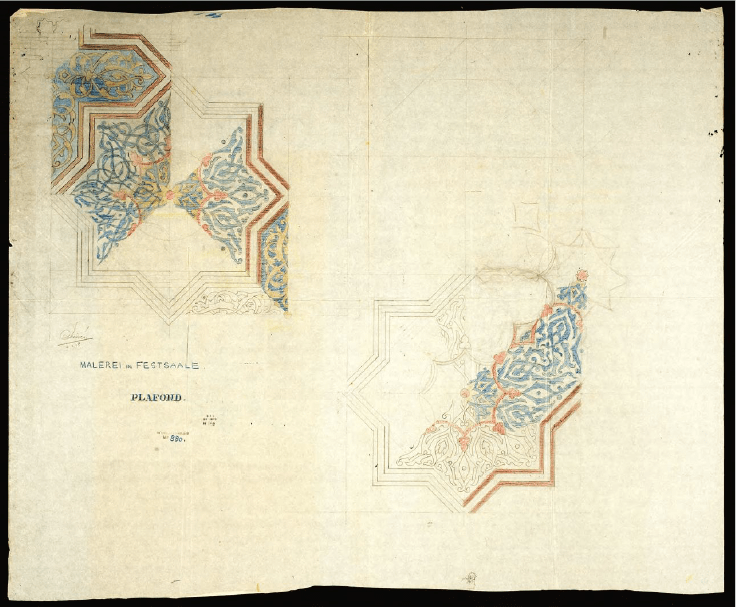

The main lobby is covered by a stained-glass dome decorated with a pattern of interlocking star polygons that seems to have been taken directly from one of the catalogues of “Arabic ornamentation” in vogue when the German architect Friedrich Maximilian Hessemer published his in 1842. A stairway in this room leads to the mezzanine-level gallery, which stands on a colonnade of horseshoe arches with decorative capitals. The stairway landing also features geometric patterns in colorful stained glass, covering the whole surface of the twin windows and the rose window above it.

Like the wall decorations, the carved or cast features on the facades and interiors were done in a neo-Moorish spirit that is the culmination of this style in Bosnia-Herzegovina. They combine decorative elements that originated both with Mamluk-era monuments in Cairo and with Fatimid-era buildings in the Maghreb. The two-color façade, simulating an ablaq building, represents a condensed version of the Islamic architecture of Egypt: niches with Persian arches and a tympanum with circular medallions drawn from Fatimid monuments; a colonnade of horseshoe arches inspired by the open galleries of Mamluk palaces; great embedded spiral-fluted columns similar to those of the Mamluk mosque of Sultan Hassan; and the row of œil-de-bœuf windows framed with cabochons and curly molding found on the façades of late Ottoman madrasas. As for the interior decoration, it is treated in the Alhambran style, with broad usage of multifoil horseshoe arches and latticework.

Over time, the function of city hall has changed several times. In 1910, the building housed the new parliament founded after the province was officially annexed to the Empire in 1908. On June 28, 1914, Franz Ferdinand, crown archduke of Austria-Hungary on an official visit, was received here with his wife shortly before being murdered by Gavrilo Princip, a Serbian student and member of the Young Bosnia revolutionary movement.

Its original usage, strictly administrative, was then replaced by scientific, cultural, and artistic purposes in response to the aspirations of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Since 1951, the date when the national university library was installed in the building, the word “Vijećnica” has been synonymous with the country’s culture and spirit.

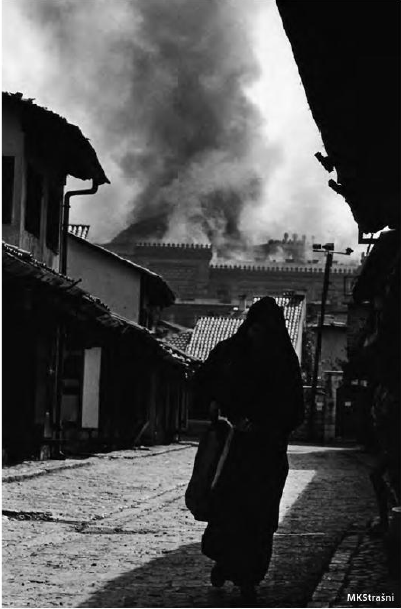

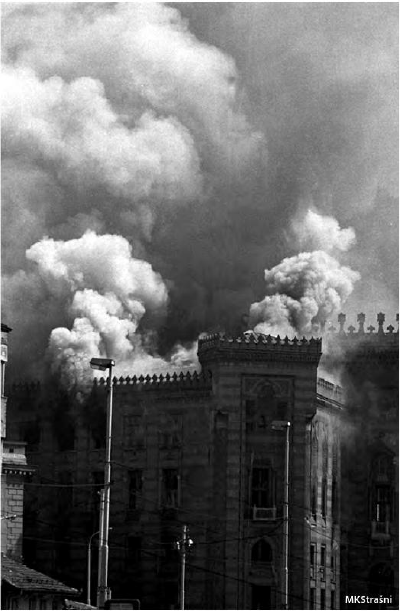

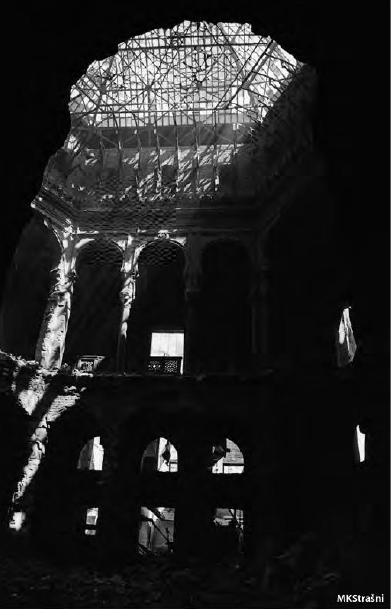

In August 1992, during the siege of Sarajevo, the building was burned and partially destroyed. An identical reconstruction began in 1996. In May 2014, after 18 years of work, the Vijećnica reopened. It has become one of Sarajevo’s most symbolic places.

In 1996, the project was launched to rebuild the building to its original state. In May 2014, after 18 years of renovation, it reopened its doors and became one of Sarajevo’s most symbolic landmarks.

Artistic looks

With his film Vijećnica, Nicolas Callaway offers an animated short film designed with rubber stamps that reproduce the geometric patterns of the scenery. The elements come to life as they are constructed, deconstructed and turned upside down, reflecting the tormented history of this emblematic building.

Artists

Nicholas Callaway

Licence

CC-BY

Words of people

About these films

Architects, neighbors and a poet tell us about the construction, fire and restoration of the town hall, and the place it occupies in their work and imagination.

Production and editing

Diogo Pereira et Sanja Vrzić

Documentation

Adisa Džino Šuta, Ivana Roso and Farah Račić

Licence

CC-BY-NC-ND

Educational activities

The Vijećnica's Decorative Patterns

Download the educational activities in English

Download the educational activities in Spanish