Location

Béjaïa, Algeria

Year of Construction

1902

Architectes et artistes

Bonnell Pierre (1850-1924)

History

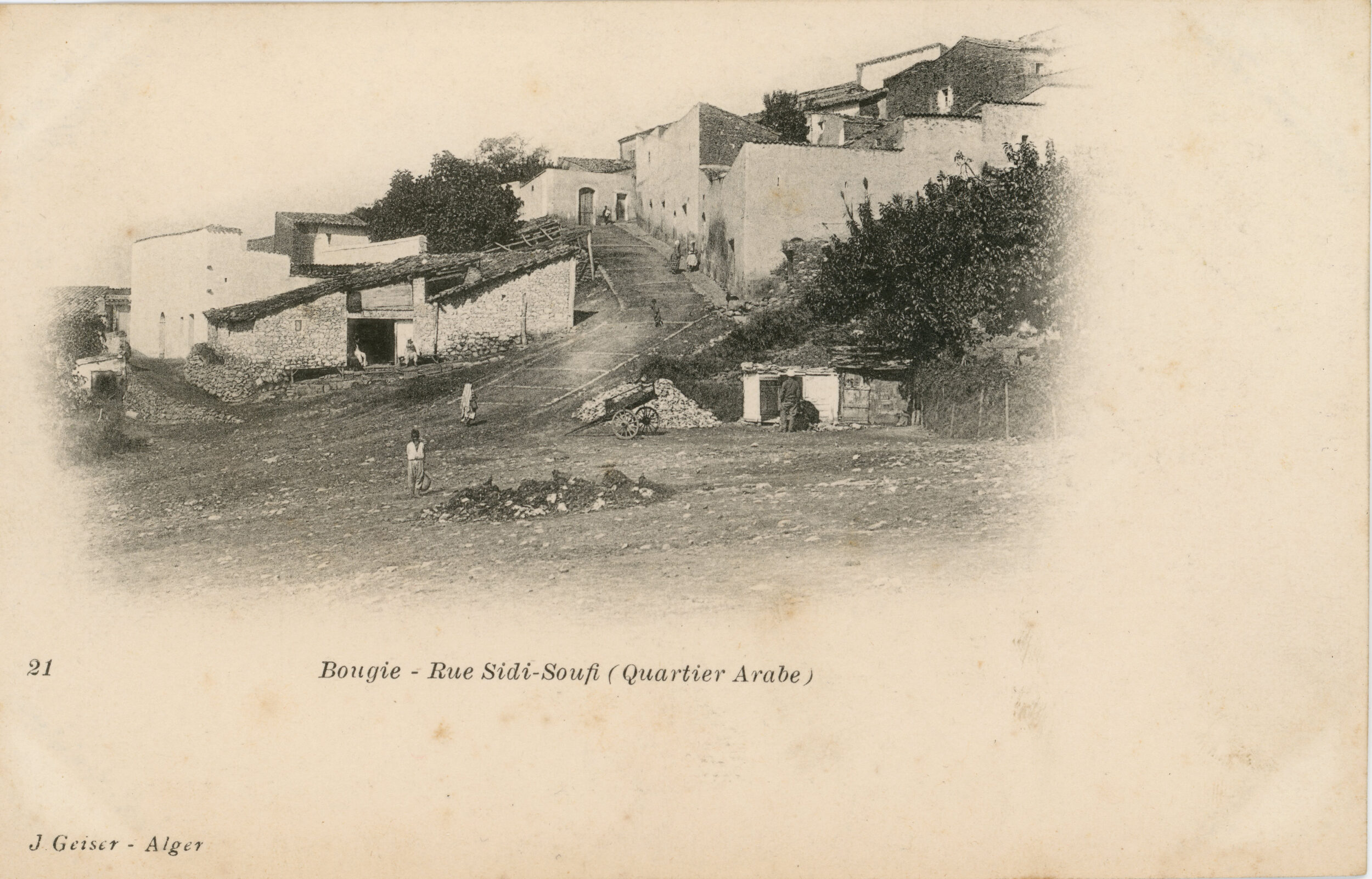

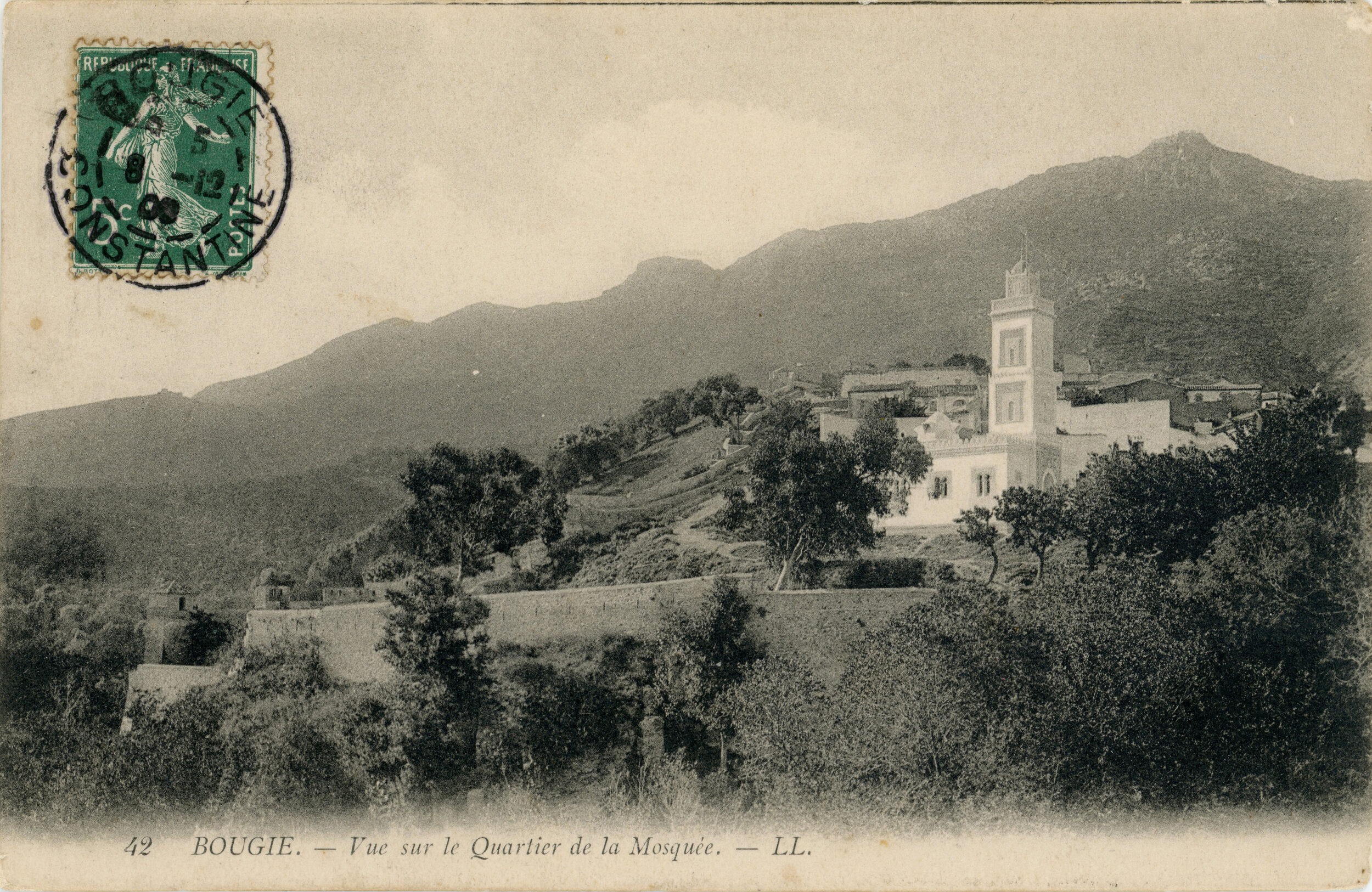

Sidi Soufi Mosque is probably the most famous one in the city of Bejaïa. Yet its history is still difficult to trace.According to the chronicle of Al-Warthilani, a traveler who visited the tomb of Sidi Soufi in the mid-18th century, the holy man was one of the most prominent celebrities of the city. When he died, a monument may have been erected at his grave site, to honor his remains and welcome visitors. According to another theory, an edifice founded on an unknown date was the mystic’s favorite praying place, and allegedly took on his name in memory of his frequent visits. Whichever is true, in 1833, when an initial map of the city was established by the French military staff, it showed a mosque called Sidi Safi (or Sidi Souffour) in the neighborhood of the current mosque, between the Fouka gate and the square then named for Louis-Philippe. The small mosque building was also used as a Koran school until 1850, when a space dedicated to teaching was arranged in an adjacent structure, the classroom section of the mosque having been condemned. The launch date for the construction of a new mosque had not yet been announced. The launch date for the construction of a new mosque had not yet been announced. In 1852, a city alignment plan provided for a new site where a large structure housing “a mosque, Muslim schools, and the Imam’s dwelling.” It opened onto a large plaza called “Place d’Armes”. But nothing happened. In 1900, the old mosque was still one of the only ones still attended in the city, but it was judged too small to welcome worshippers. None of the sources available today seems to document the works on the new edifice. Nevertheless, it is known that the Sidi Soufi Mosque of today, located slightly south of the original building, officially opened on May 23, 1902. The name of its designer is not indicated by the sources. The architect may have been Pierre Bonnell, appointed in 1901 to supervise diocesan construction in Constantine. As early as 1889, Bonnell had been working on a project to build a beachfront boulevard.

From an architectural viewpoint, today’s mosque presents a compact basilica plan with three naves and six bays. The naves are oriented perpendicular to the qibla wall where the mihrab is installed. Since the door to the prayer hall is on the square (formerly called Place Louis-Philippe, now called Place Sidi Soufi) also located to the east, the qibla is in a strange location beside the entrance portico. The current floor plan is the result of extension works carried out in the 1930s (paid for by public subscription in 1933 and opened in 1939). Originally, the prayer room was square with three naves and three bays. The central bay of the central nave was topped with a polygonal dome (still extant). The absence of a courtyard is fairly common in colonial-era mosques. The composition of the façade, however, is more reminiscent of a Christian church of the time, with a portico steeple, the classical 19th-century reference to portico steeples of the Romanesque period.

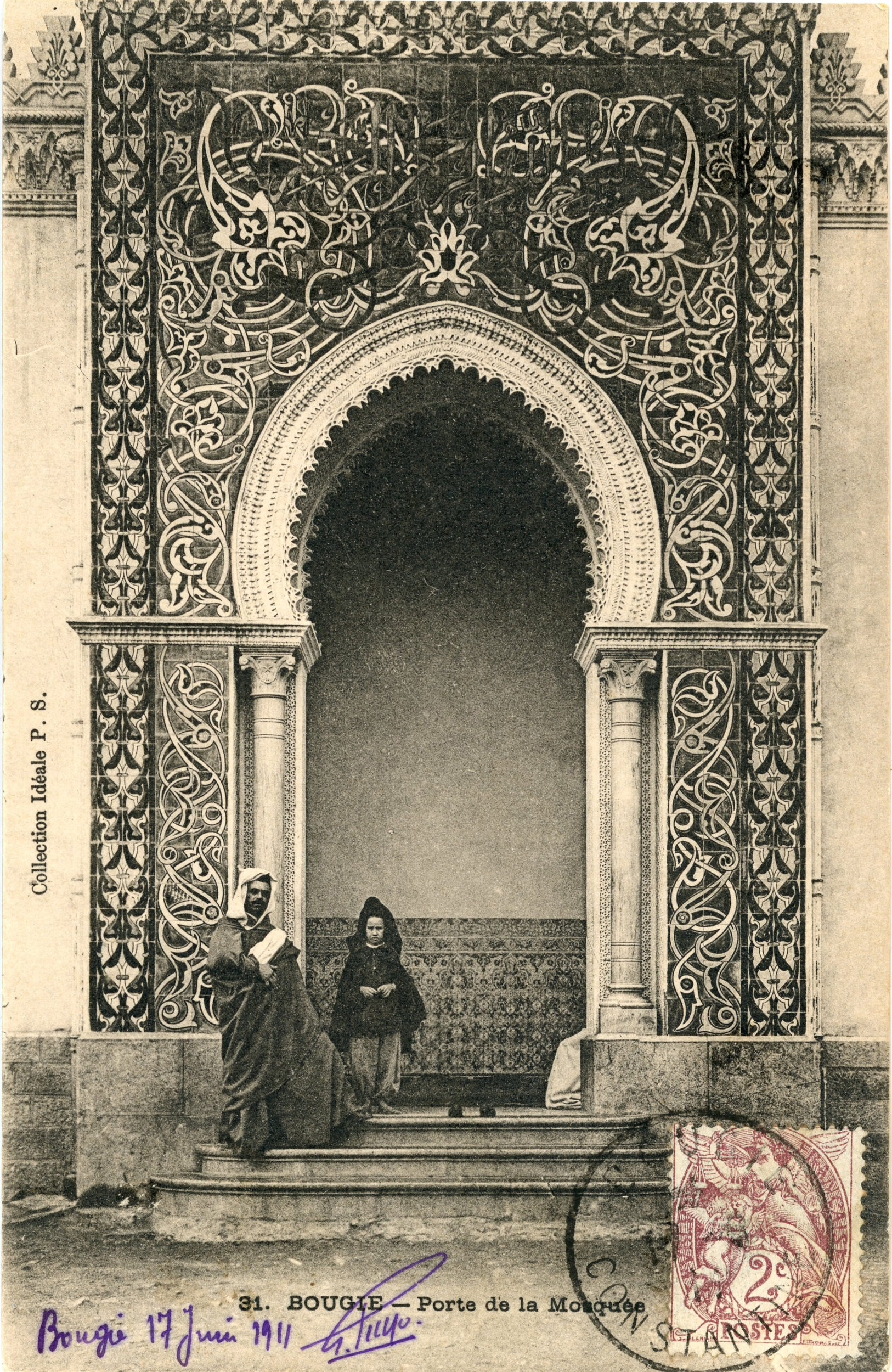

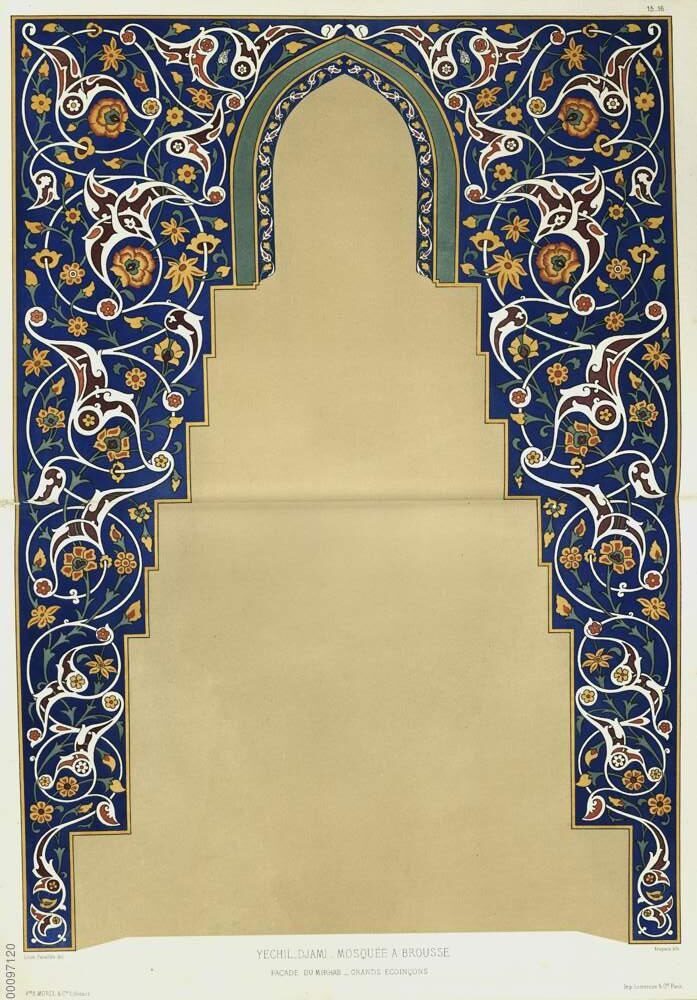

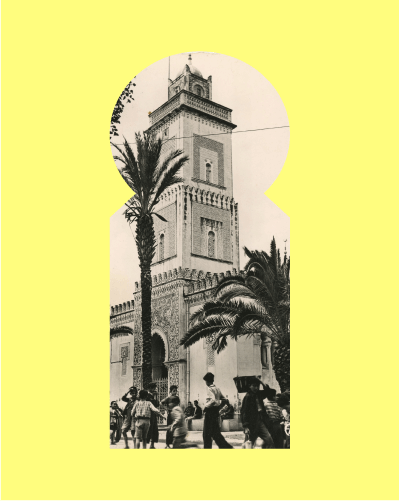

The mosque’s originality lies more in the ornamentation of the portico than in its structure. The tiles were designed by ceramicist Ernest Soupireau. The entrance is formed by a broken horseshoe arch with a delicately carved scalloped inner surface supported by two small, slim colonettes with carved capitals. This arch is in the center of a large panel of polychrome ceramic tiles displaying a vision of foliated scrolls with palmettes and fleurons. Against this background of plant motifs, the basmallah is inscribed in the naskhî calligraphic style. The merlons on the crenellated compound walls are decorated with carved palmettes, crowning a sculpted frieze imitating the muqarnas pattern. On the minaret itself, the three registers of windows are framed by ceramic panels with geometric or plant-related designs.

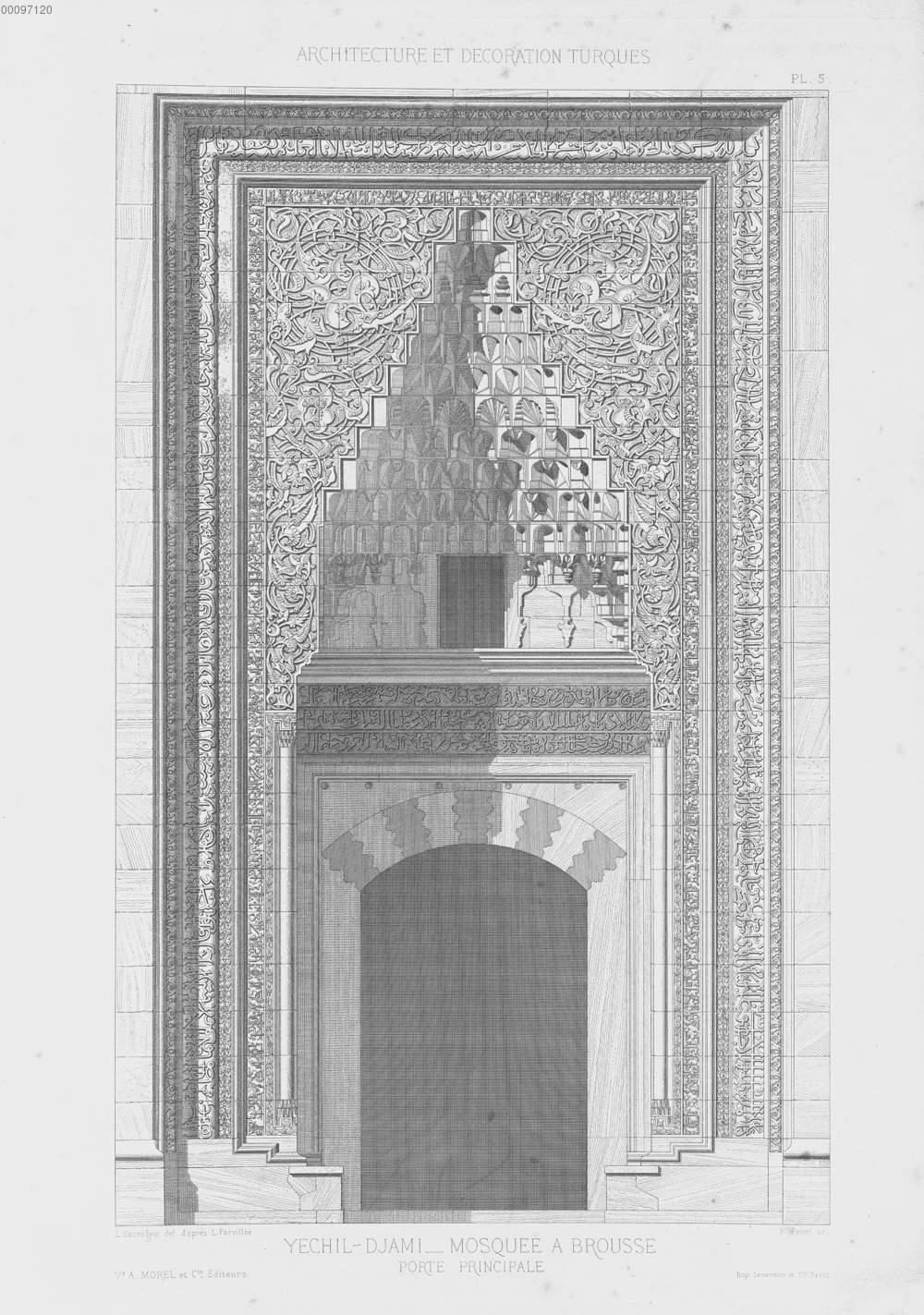

The structures decoration and architectural forms attest to an unbridled orientalism blending references to Moorish-Spanish architecture (in the shape and openings of the minaret, for example) , with those of much more distant, Ottoman Turkish provenance. Actually, the large plant design at the entrance imitates the carvings on the entrance to the great mosque of Bursa, known as the Green Mosque, erected between 1419 and 1424 by order of Sultan Mehmed Çelebi. The latter mosque had become famous in France, thanks to a replica made by Léon Parvillée at the Trocadéro for the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris. In 1874, a book about the mosque’s decoration, copiously illustrated with color plates, was published. In Algeria, the Oriental inspiration may seem surprising, but Ernest Soupireau commonly employed it, and references to the tiling of the Ottoman mosque can be found in several pieces he made for private individuals. Actually, he had also made a copy of the ceramic facing on the Bursa mosque for the 1907 Exposition de la Médersa in Algiers. The following year, the piece was exhibited in London at the 1908 Franco-British Exhibition, where it was a great success.

The mosque was immediately greeted with enthusiasm, and in 1905, le newspaper L’Écho de Bougie reported that when Charles Jonnart, Algeria’s governor-general, visited the city, he “contemplated the strange and gracious monument, wedding all the styles of the lands of Islam unconsciously, for a long time.”

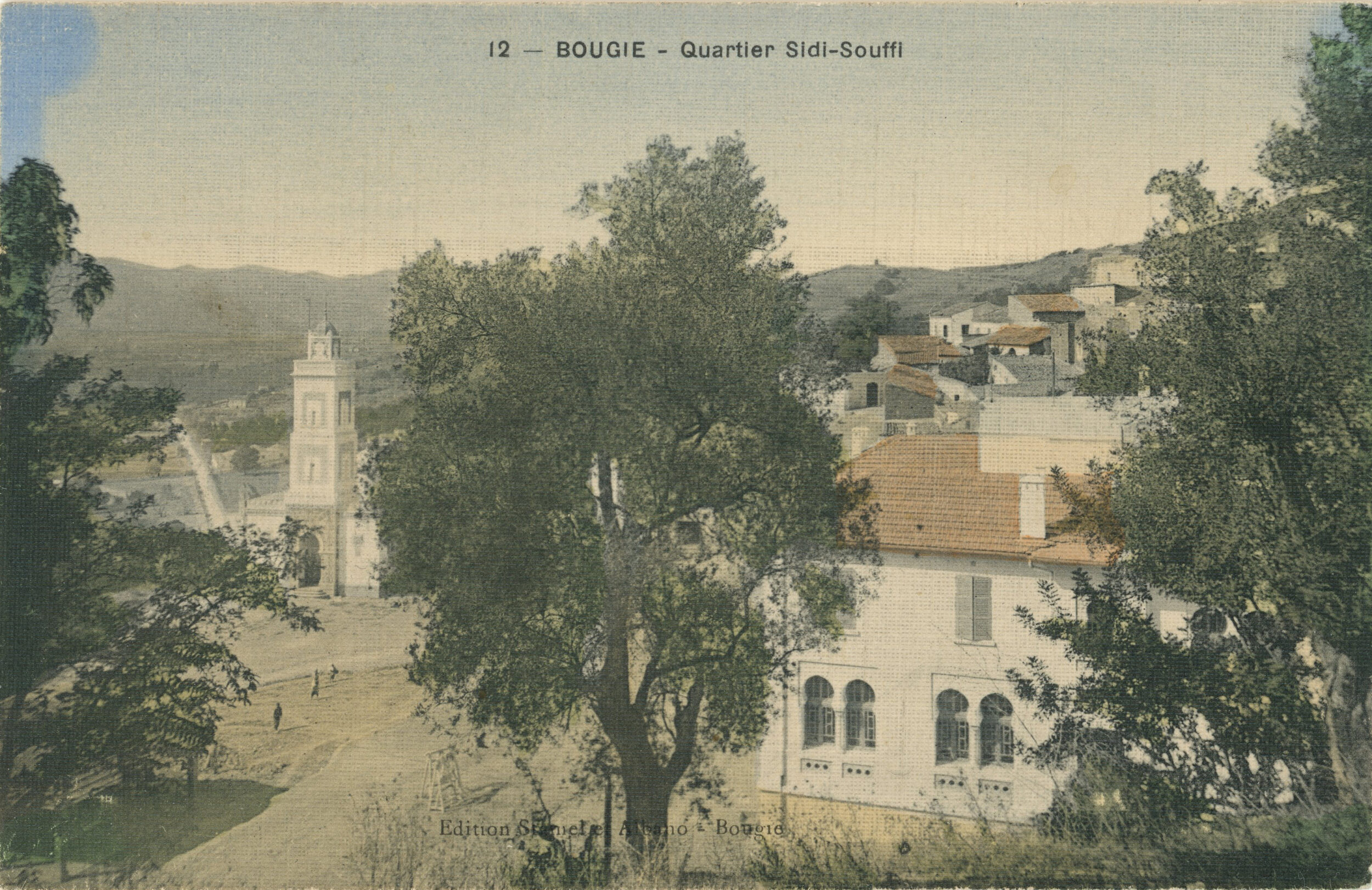

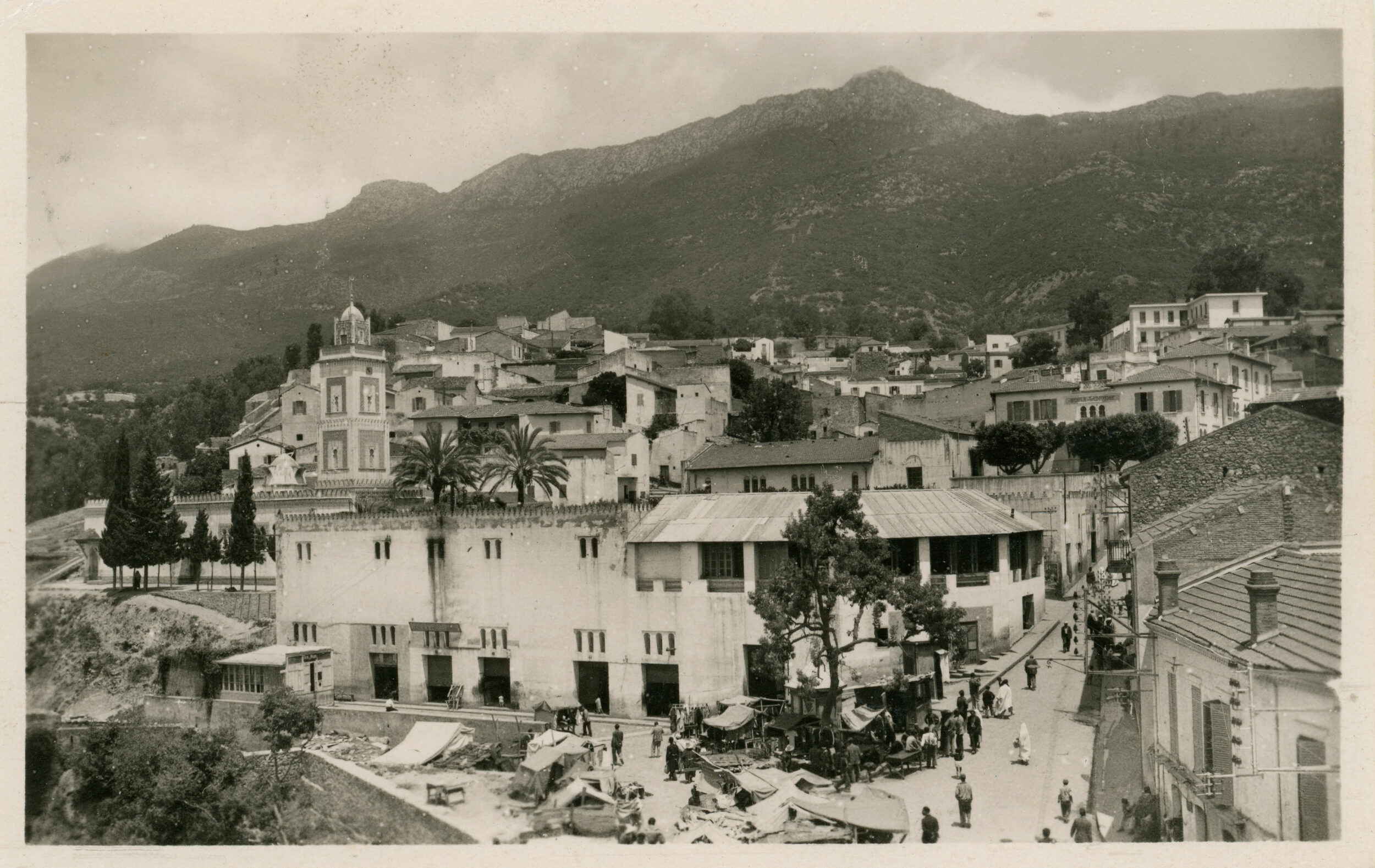

From an urbanistic viewpoint, contemporary views first show an isolated building overlooking a sloping mall made of packed dirt. To the west, it ends with a small covered marketplace. In the same period, an “indigenous school” for boys (currently the CEM El-Hadi Zerrouki) was built on the plot overlooking the mall from the north.

During the interwar period, the esplanade was graded and several public buildings, all in the neo-Moorish style, were constructed around it and in neighboring streets. For example, in 1928, souk marketplaces were built along the southern edge of the plaza (they were expanded in the 1950s). A public bathhouse (opened in 1939) was built on the street leading to Bab Fouka. Today, this urban compound is one of the crown jewels of Béjaïa’s architectural heritage.

Words of people

French transcription

English transcription

Spanish transcription

About this audio

The Sidi Soufi mosque, very popular with local residents, is for them one of the jewels of the local neo-Moorish style.

Interviews and writing

Sami Boufassa, Juliette Hueber, Claudine Piaton, Hamid Rahiche, Bulle Tuil Leonetti

Editing

Éléonore Clovis

Audio mixing

Alban Lejeune, It Sounds Good

Licence

CC-BY-NC