Location

Tozeur, Tunisia

Year of Construction

1910-1912

Architectes et artistes

Pucciarelli Almo (?-1951?)

History

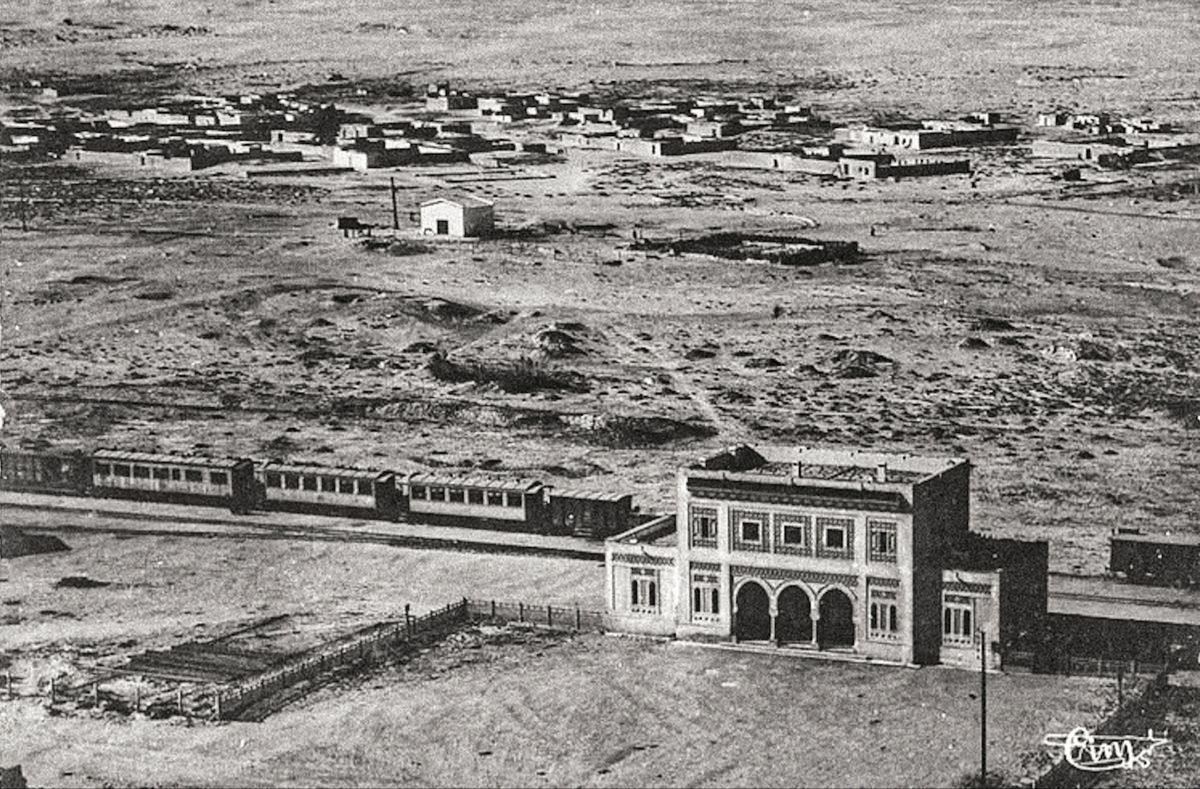

The history of the construction of Tozeur railway station is indissociable from the history of the Compagnie des Phosphates et du chemin de fer de Gafsa. This colonial enterprise was founded in 1896 to mine phosphate deposits in the Metlaoui region of southern Tunisia[1]. In 1899, the company completed the Gafsa-Sfax line to move ore towards the Mediterranean. It then signed a contract with the Tunisian government in 1904 to study extending the rail line to the oases at Djérid which was, according to the company, “the biggest population center in inland Tunisia, undoubtedly likely to attract crowds of tourists and winter residents.” At its 1910 shareholders’ meeting, the company reported on the advancement of the Metlaoui-Tozeur line. The project had just been approved by the executives of the public-works department, and construction was set to begin[2].

To build this public infrastructure, the government did resort to financing from the private corporation, which was then reimbursed by being exonerated from taxes and duties on its mining activities.

The exact date when works on the station began is unknown, but can be estimated to have been circa 1910. The building was completed shortly before the 1913 opening of the rail line, as attested by a report on a visit from the members of the French Association for the Advancement of the Sciences. They remarked upon “the varicolored brick mosaic of Tozeur station, shiny and brand-new.”[3]

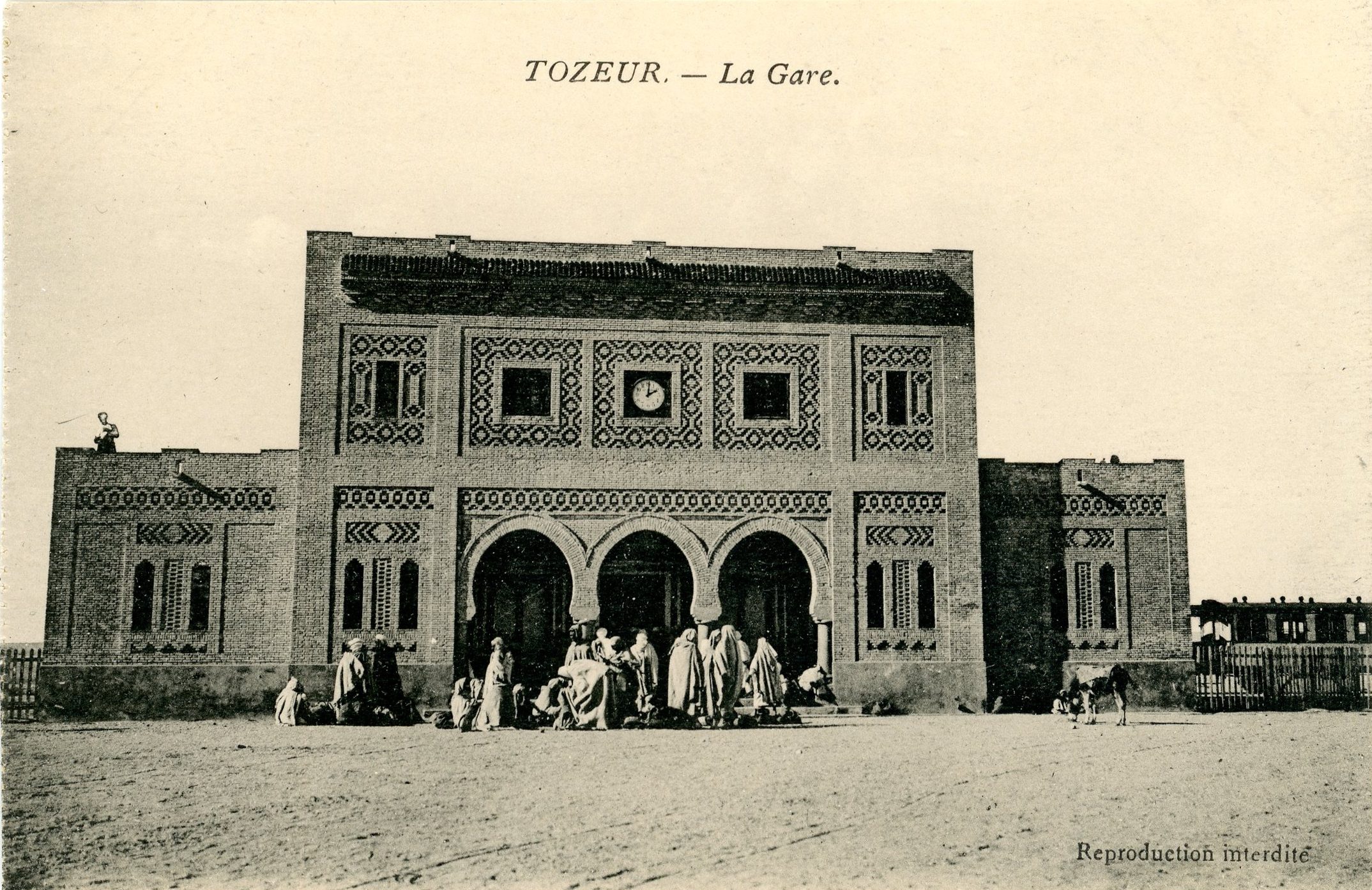

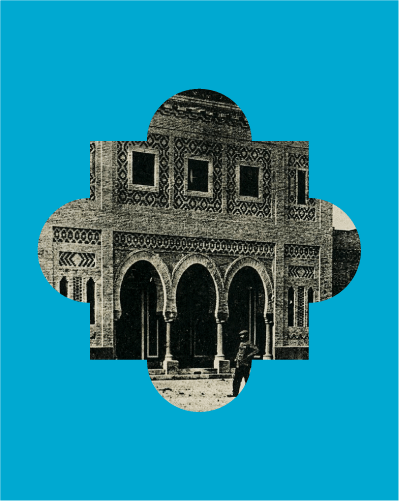

Probably designed by company engineers, the building belongs to the common typology of rural stations of the French rail network. Typically, the project included the ticket lobby, luggage service, waiting room, and stationmaster’s dwelling. Like the station at Sfax, built in the late 19th century, the structure is a symmetrical composition with a large central section and two narrow naves, covered with a flat roof terrace. Unlike the station at Sfax, however, the central section is two stories high whereas the naves had a single street level.

The sleek, functional building is also distinctive due to the type of materials and façade decoration. Like much of turn-of-the-20th-century railway station design, it drew inspiration from local architecture. In this case, the regionalist concept is expressed by the use of a terra-cotta brick construction technique called škûka. It consists of producing a decorative wall facing by laying the bricks in various patterns: in horizontal bands, some of which are denticulated or herring-boned, and in a diamond-shaped mesh organized as tables around the bays.

This reinterpretation of the traditional architecture from the Djérid region[4] stands out from the neo-Moorish style of the period, in which motifs were borrowed from a variety of Islamic arts without concern for coherence with local tradition. However, the decoration does not entirely escape the clichés of the Tunisian neo-Moorish style. The tile decoration on the vestibule walls, behind the triple-arched entryway, is related to that of city dwellings in northern Tunisia. The same is true of the powerful roof moldings, covered with glazed tiles.

The style, which could be described as “neo-Djeridian,” was repeated in several of the public buildings in Tozeur (the caïdat, or municipal leader’s home; the post office; the contrôle civil, or police station; the governor’s house, and the schools), and also for one of the first hotels in the oasis, the Grand Hôtel Bellevue owned by the Disegni family. This prominent Jewish family from Livorno, who had settled in Tunis, had long been known locally for its activities in the date-palm business and tourism trade, with the publication of postcards, for example. Likewise, they were in the brick-making business. Thus, picture postcards of the station, published in the 1910s by the family, note that the bricks were supplied by none other than T. [Téobaldo] Disegni (1867-1935)[Téobaldo].

Construction has been attributed to the Italian-born contractor Almo Pucciarelli, who had established a business in Sfax. Pucciarelli is also thought to have built the “Monopoles” building (housing the tax administration) in Tozeur, built in the same architectural style.

Notes

- [1] Cie des phosphates et chemins de fer de Gafsa (Tunisie), April 3 1897.

Les mines et installations de la Cie tunisienne des phosphates du Djebel Mdilla (Tunisie), Tunis: A. Perrin, 1923. URL : https://octaviana.fr/document/FJDNM050, consulté le 18 janvier 2023. - [2] L’Économiste français, June 4 1910.

- [3] Association française pour l’avancement des sciences. 42, Compte-rendu de la 42e session Tunis 1913 ; Le Phosphate, 8 juin 1914.

- [4] Abdellatif Mrabet, L’art de bâtir au Jérid: étude d’une architecture vernaculaire du Sud tunisien, 2004 ; Diogo Pereira and Sanja Vrzić, Shapes of Earth, 2022.

- [5] Dominique Jarrassé, “En six-roues de Biskra à Djerba. Villégiature hivernale, ‘esthétique de l’oasis’ et architecture hôtelière régionaliste,” in Cyril Isnart, Charlotte Mus-Jelidi and Colette Zytnicki, Fabrique du tourisme et expériences patrimoniales au Maghreb, XIXe-XXIe siècles, Rabat : Centre Jacques-Berque, 2019. DOI : 10.4000/books.cjb.1407

Artistic looks

Shapes of Earth by Sanja Vrzić and Diogo Pereira explores the link that the station maintains with the multisecular constructive tradition of the Djerid oases, through a contemplative film which captures the process of the transformation of raw clay into brick, and then in architecture.

Direction and production

Sanja Vrzić et Diogo Pereira

Licence

CC-BY-NC-ND