Location

Toledo, Spain

Year of Construction

1919

Architectes et artistes

Clavería y de Palacios Narciso (1869-1935), Pascual Martínez Julio (1879-1967)

History

Rail service reached Toledo in 1857, linking the city to the line from Madrid to the eastern coast. At that time, the first station was built on Paseo de la Rosa, on Toledo’s outskirts, in a district where warehouses and inns were located. At the time, a large plaza with gardens and space accessible to travelers and carriages was planned, near the main building. This station, designed by architect Eusebio Page Albareda, resembles those in neighboring cities like Castillejos, Torrijos, and Bargas. The two-story building was plain and conventional, devoid of decorative elements. The two-story building was plain and conventional, devoid of decorative elements.

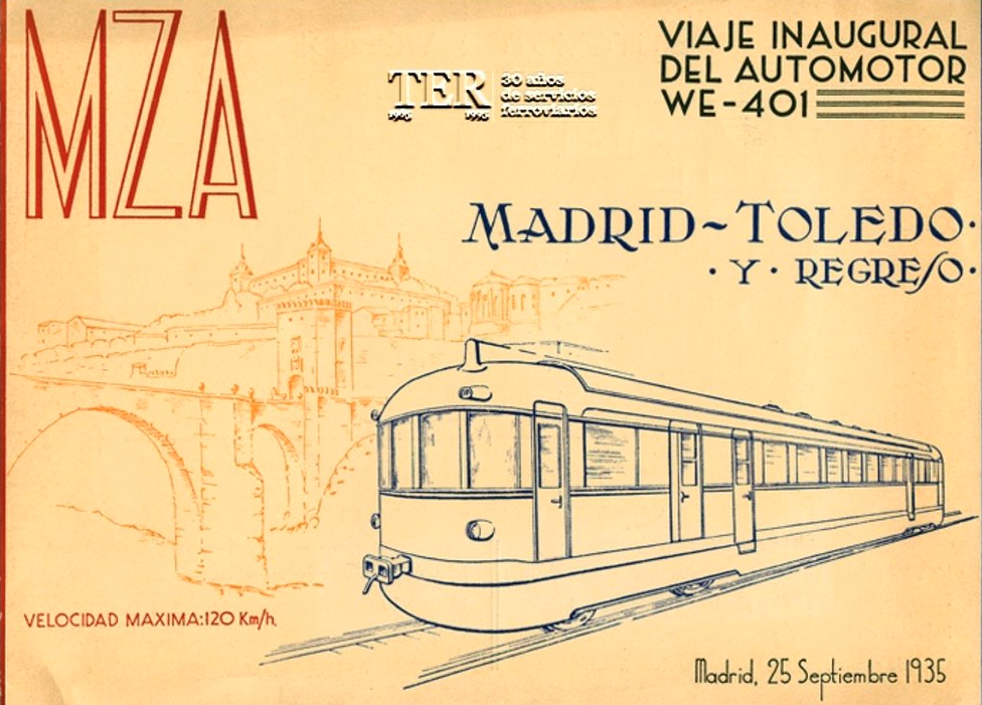

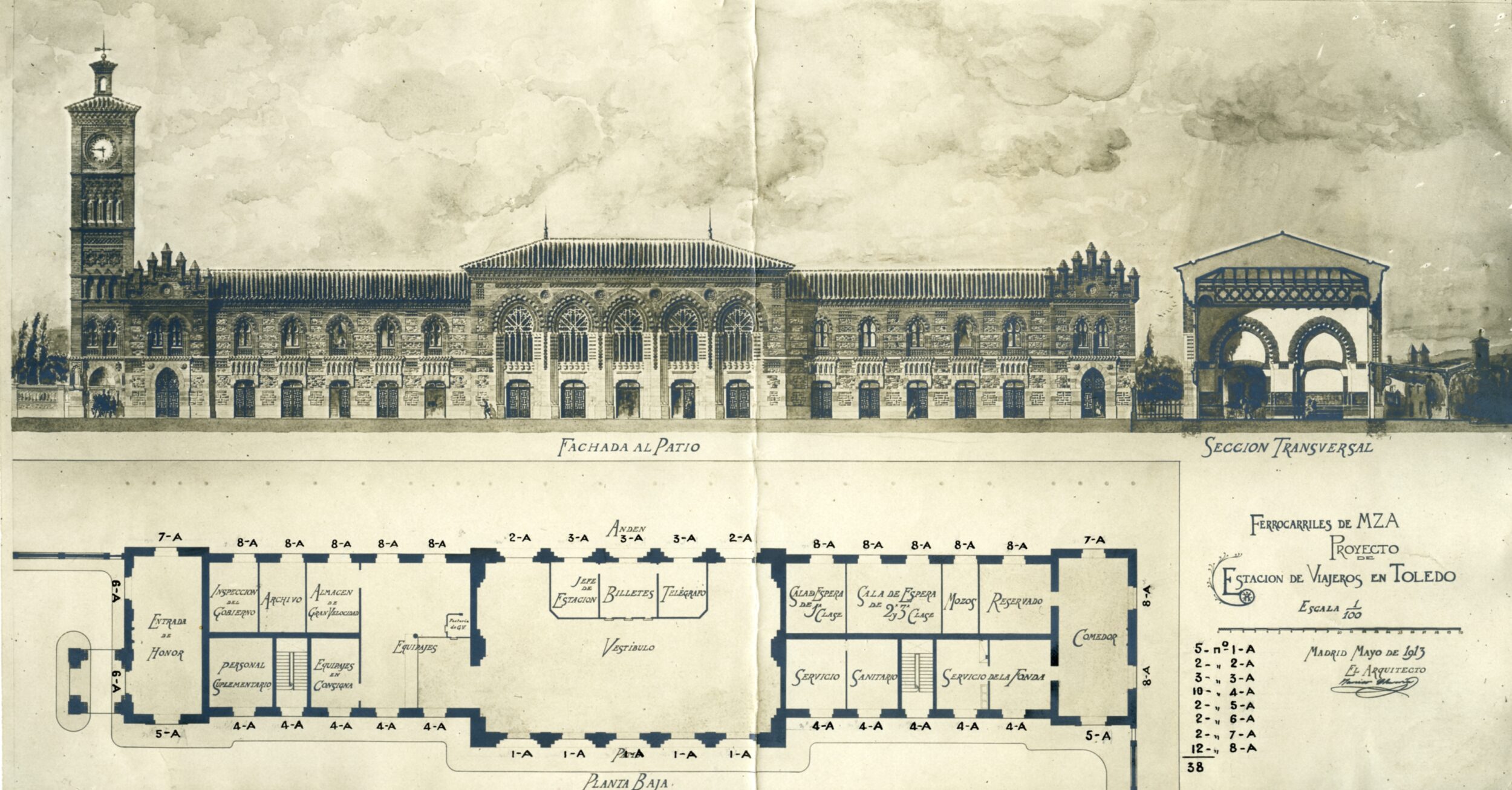

In the early 20th century, increased passenger traffic spurred plans to replace the old station with a new one. Spanish king Alphonse XIII (1886-1941) became directly involved with the project. The idea was to endow the station with architecture worthy of Toledo’s history as a capital city. The Madrid-Zaragoza-Alicante (MZA) Railway Company supervised the project, commissioning architect Narciso Clavería y de Palacios, third Count of Manila. Clavería y de Palacios had previously worked in Madrid with his master, Juan Bautista Lázaro de Diego. Ground was broken in 1914 with French engineer Édouard Hourdillé supervising the construction. The works were managed by MZA engineer Ramón Peironcely Elósegui. The ribbon was finally cut on the new station in 1919.

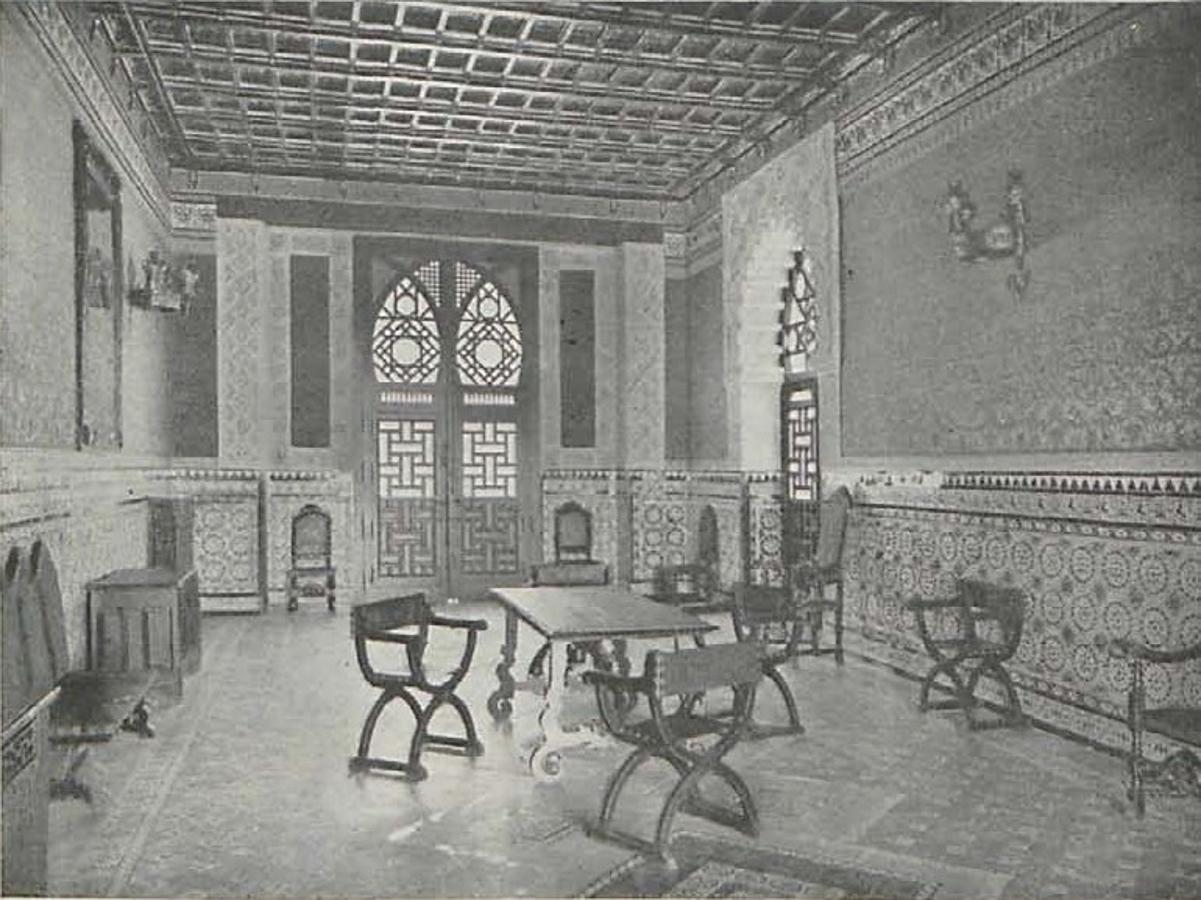

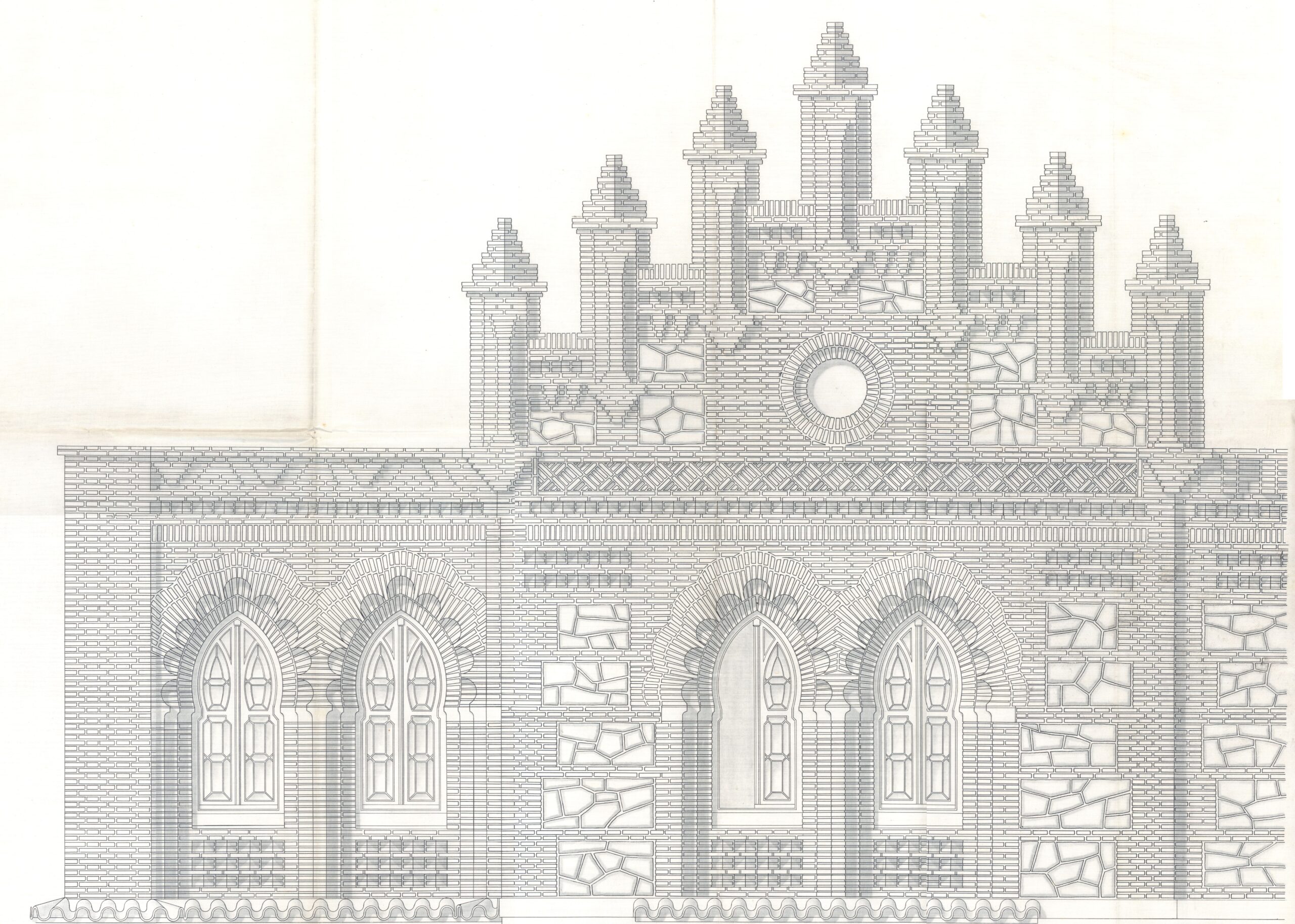

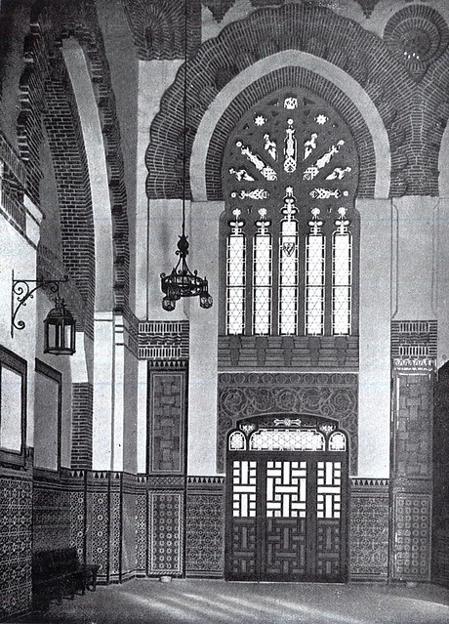

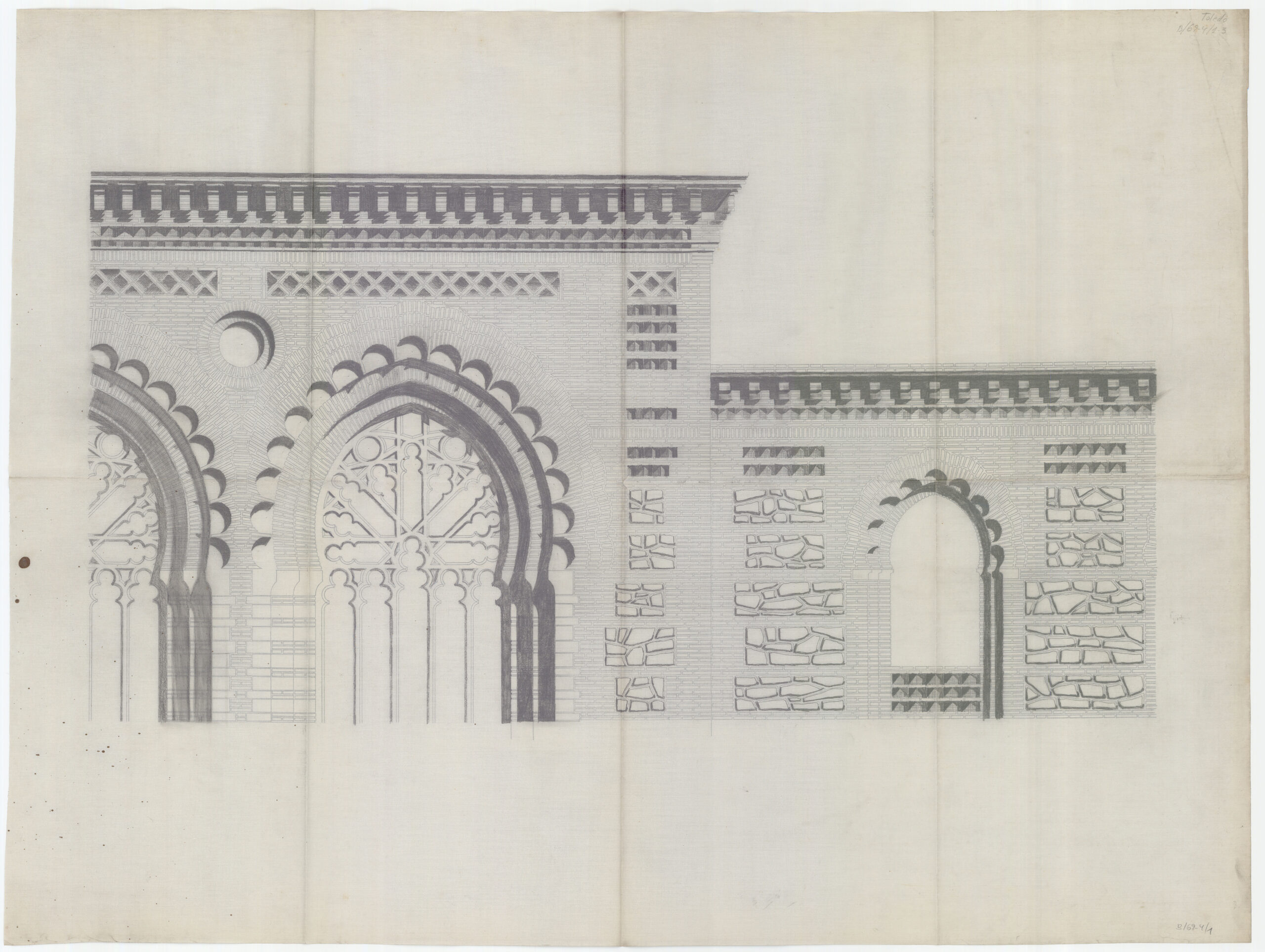

The main building consists of a vast single-level central section lit by large tinted-glass windows. It houses the ticket windows and concourse. Two two-story naves contain the reception rooms and a cafeteria on the ground floor, with housing for personnel upstairs. Clavería adopted a neo-Mudéjar style for the naves, inspired by the Toledan convent of Santa Isabela de los Reyes, featuring multifoil horseshoe arches, crenellated merlons crowning walls decorated with interlocking arch frameworks and a mesh of diamonds. Local contractors Antonio Dorado and Eduardo Rivero carried out the decorative work. A monumental tower, reminiscent of the Teruel Mudejar style–the steeples of San Pedro and San Martin, to be exact–connects the platforms to the outdoor mall. This passage is reserved for distinguished visitors.

The quality of and care for the architectural decoration attest to the knowhow of the artisans, associated with the Toledo school of arts and trades. The plasterwork, inspired by that in the synagogue at Santa Maria la Blanca, was carved by Ángel Pedraza Moriz. The ironwork railings, grills, lamp pillars, lamps, and wall-mounted lamps were designed by the famed master ironworker Julio Pascual Martínez. The ornate mirrors in the reception hall were the work of young designer Cristino Soravilla y Rózpide. Paneling and classical-style furniture were commissioned from cabinetmaker Jaime García Gamero, whose workshops were located in Santo Domingo el Real. All these craftsmen were trained at the school in Toledo, where several of them later became instructors. Nevertheless, certain components were ordered from other sources, like the ceramic tile, produced by the Hijos de Justo Vilar works in Manises (Valencia).

The use of historicist Neo-Mudéjar language in railway architecture is not surprising. It was also employed in the construction of other stations like the one in Huelva, designed by Jaime Font y Escolá in 1880 and the Seville-Plaza de Armas station, the work of engineer José Santos Silva in 1901. Later, Jerez de la Frontera railway station, linked to the 1929 Ibero-American Exposition in Seville, can be cited. Clavería himself adopted the Neo-Mudéjar again for other stations in Madrid province, like Algodor (1920), now abandoned, and Aranjuez (1922). The Toledan plans had nevertheless sparked a lively debate opposing advocates of historicist language and those who, like engineer Vicente Machimbarrena Gogorza, director of the Escuela des Caminos, demanded “asepsis” and an economy of means more in keeping with the industrial nature of the building.

Toledo railway station, declared a Property of Cultural Interest in 1991, was restored in 2015, when the high-speed train line was extended to Toledo.

Words of people

About the film

Local residents, users and historians share their admiration for this symbol of Toleban neo-Mudéjar architecture and the skills of Castilian craftsmen.

Speakers

Clara Ilham Álvarez Dopico, Pilar Gordillo, Eduardo Sánchez Butragueño, Luis Sazatornil Ruiz

Interviews and writing

Clara Ilham Álvarez Dopico

Filming and editing

Mirage illimité

Music

Dancing Upside Down by Aitua (Elements)

Licence

CC-BY-NC-SA

Educational activities

Toledo Railway Station Patterns

Download the educational activities in English

Download the educational activities in Spanish