Location

Oran, Algeria

Year of Construction

Fin XVIIIe-XIXe siècles

Architectes et artistes

Combarel Edmond (1817-1869)

Contemporary photographies

History

The Bey’s Palace is one of the rare Ottoman-era monuments to have been preserved in Oran. Its appearance and complex history reflect the tumultuous past of the city of Oran, occupied successively by the Spanish and the Ottomans prior to capture by the French in 1831.

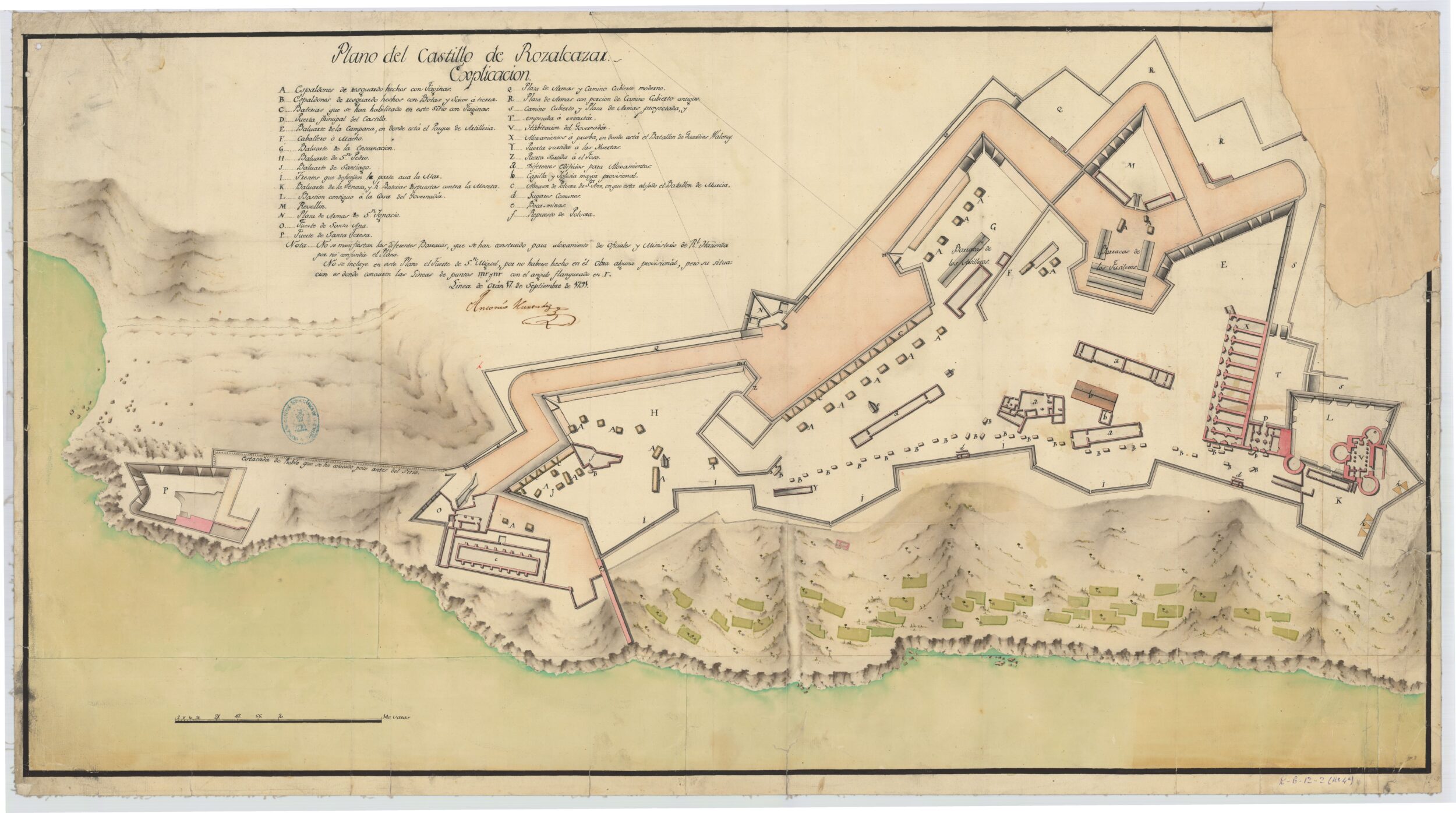

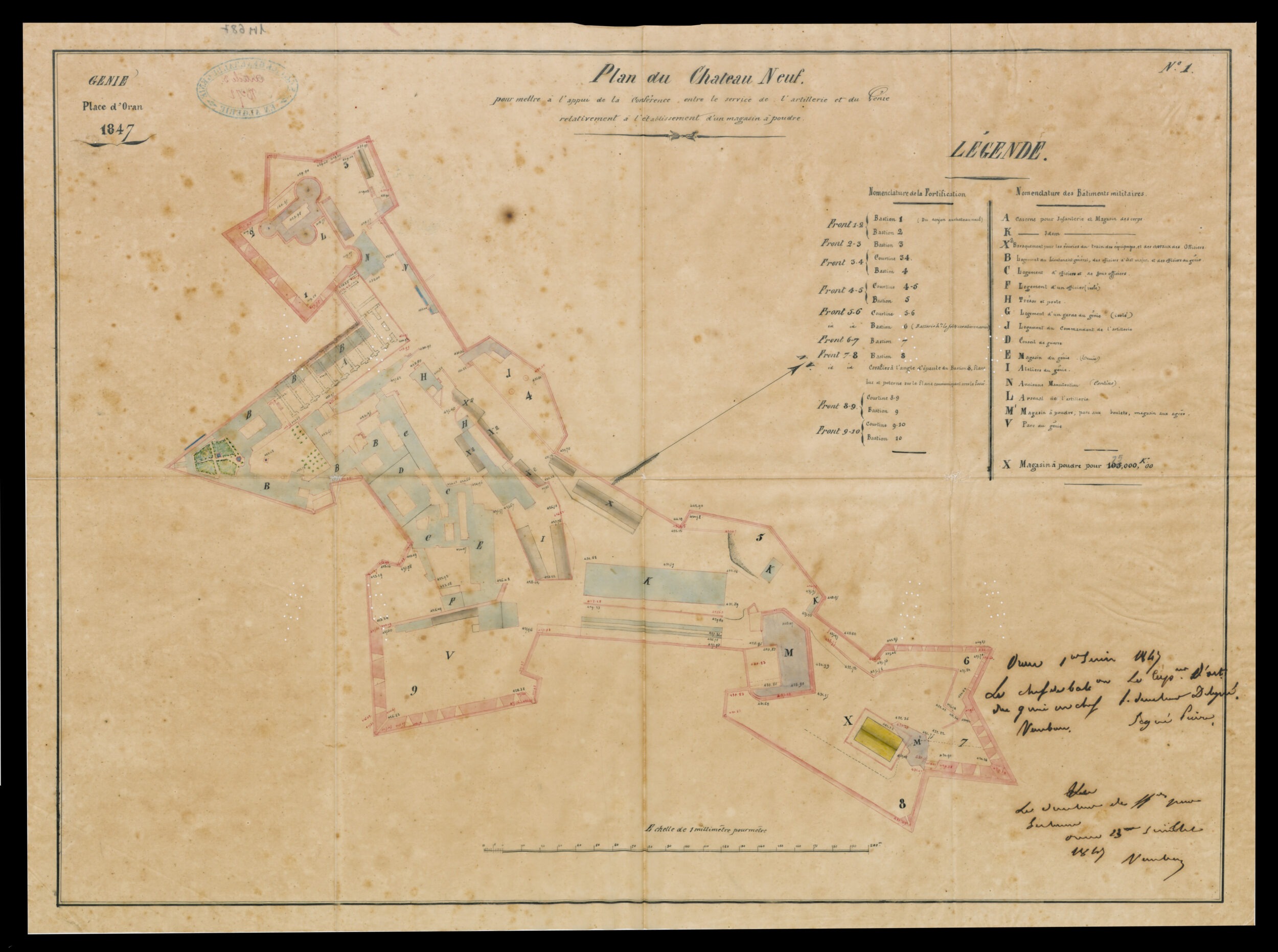

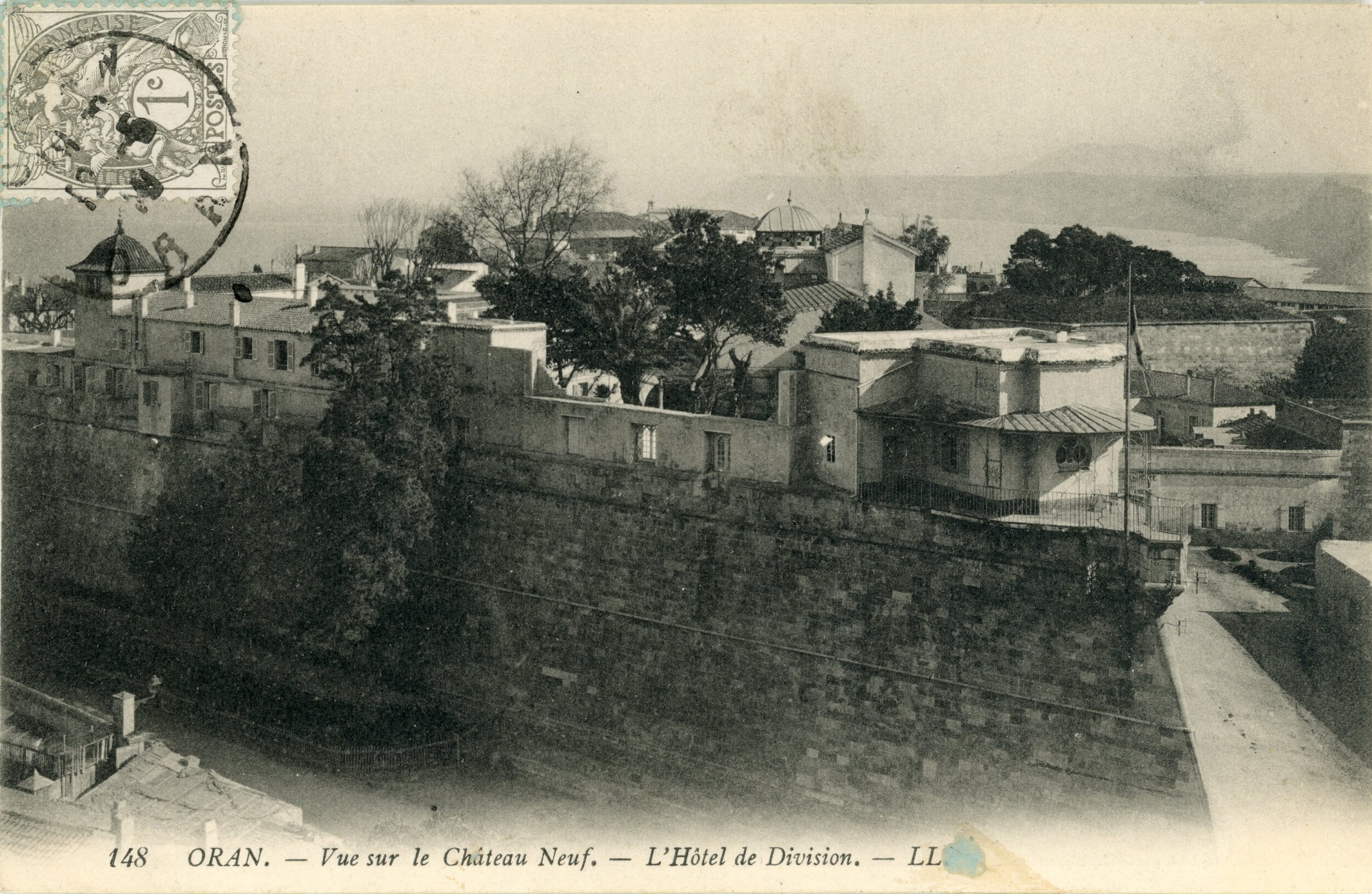

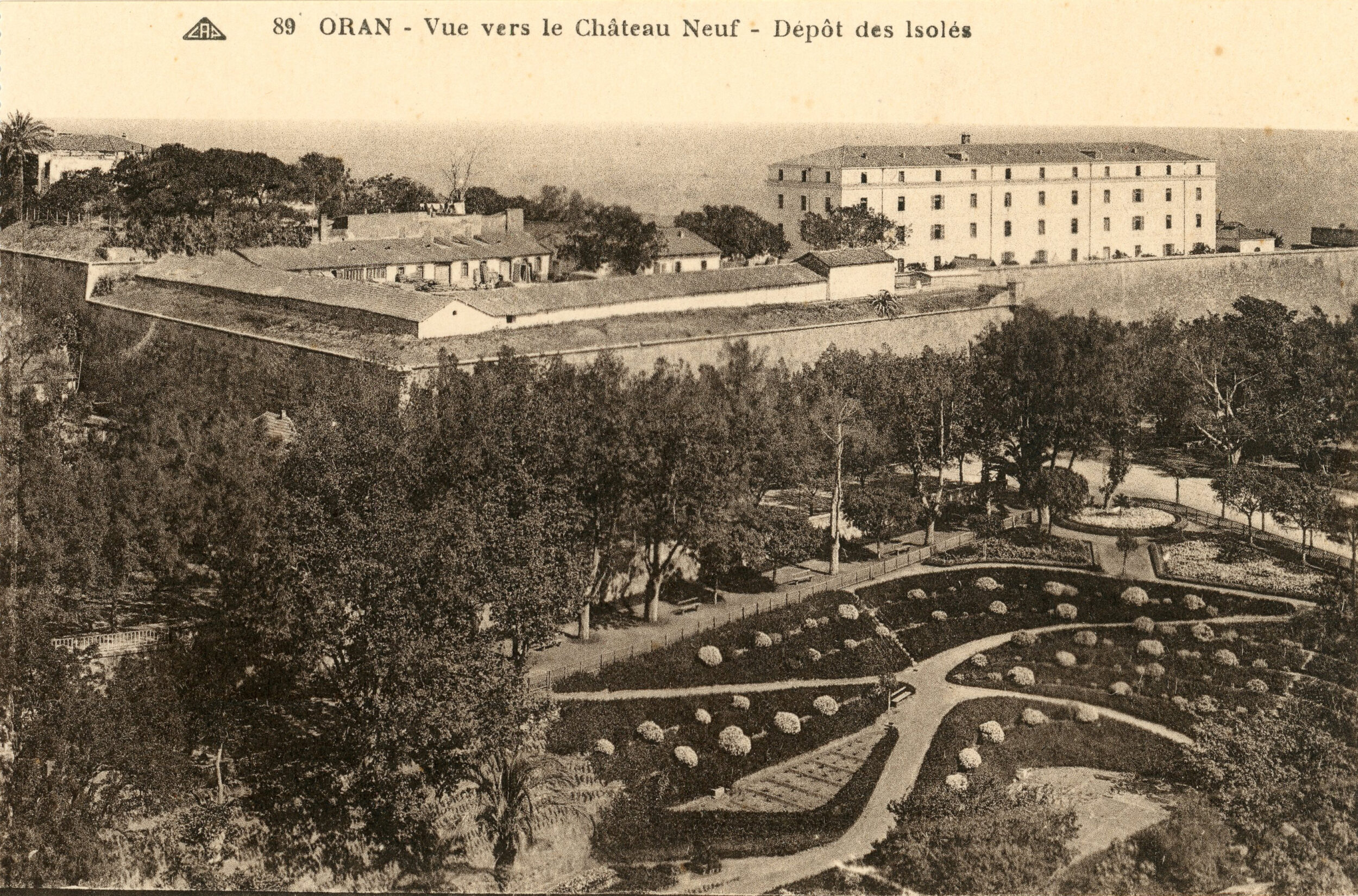

The Palace is located in the Rosalcazar fortress compound, built after 1509 by the Spanish. Between 1792 and 1831, when the Ottomans occupied Oran, the fortress became the residence of the Bey Mohammed el-Kebir. His successors then erected several other buildings. In 1831, the French military command, considering the fortress the city’s most secure stronghold, established its headquarters in the palace.

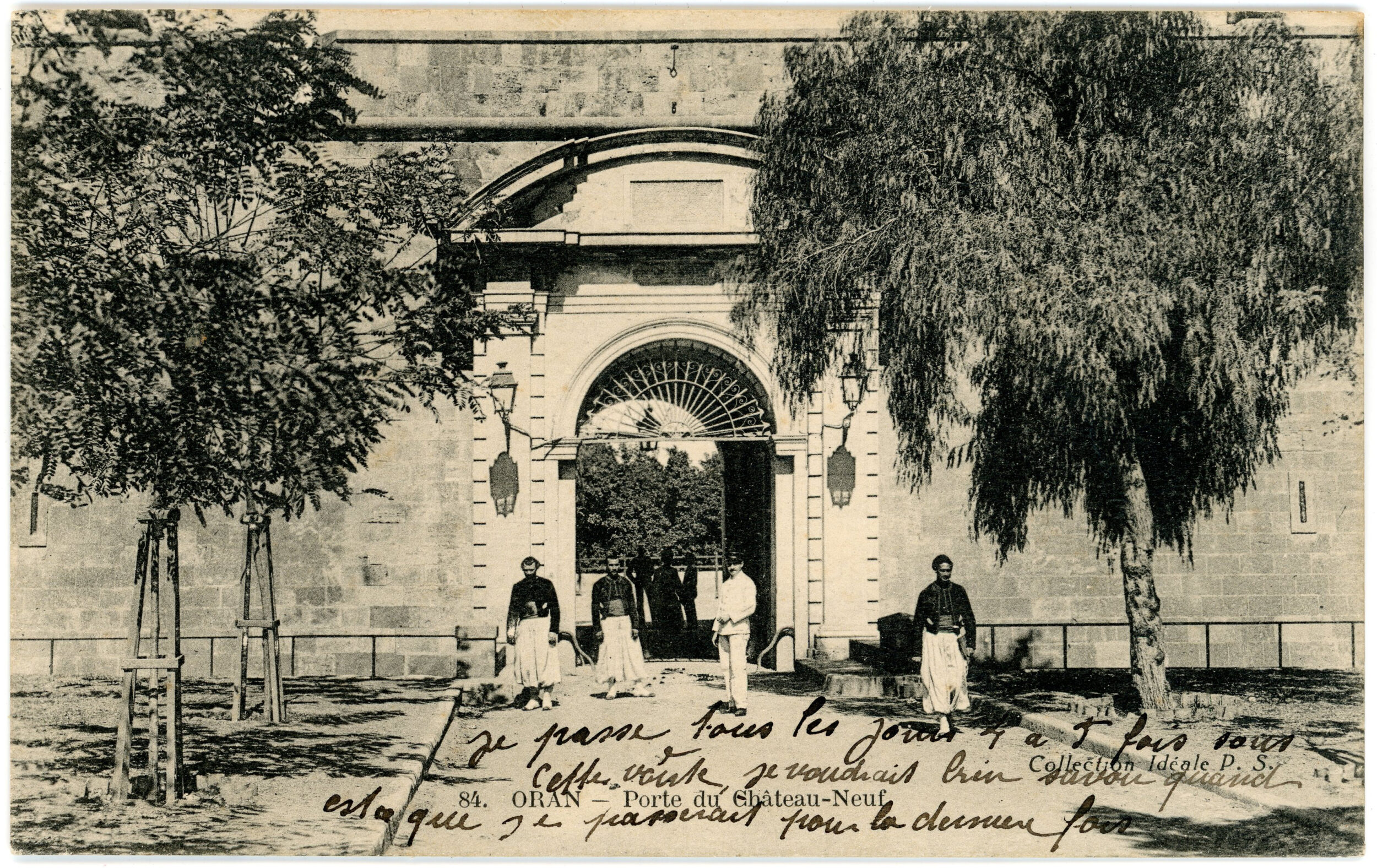

The palace stands on the uppermost terrace of the Spanish fortress, between bastions 9 and 10 and the monumental gate bearing an inscription commemorating its completion in 1758.

The vast dwelling is divided into two compounds: the French Army Corps of Engineers staff offices and living quarters (buildings demolished after Algeria’s independence in 1962) and the Division Hall. The latter stood on bastion 10 and consisted of five main buildings. The four remaining today form “the Bey’s Palace.”

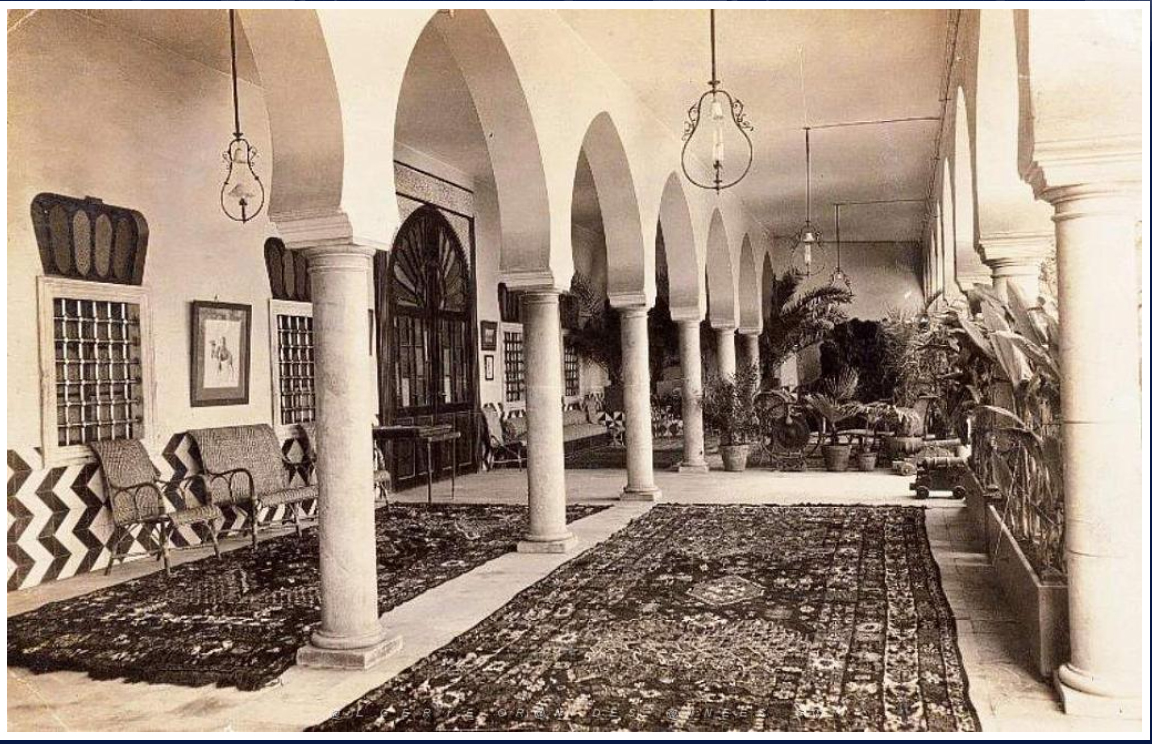

Currently, the entrance to the palace is located under a porch leading to a large courtyard. The water reservoir and pumping station built over the well in 1867 are connected to the eastern wall. In Ottoman times, they “distributed water through pipes to the various parts of the citadel.” The courtyard provides access to two buildings: to the east, a one-story wing with a patio and gallery extending to the former palace hammam, and to the south, a long wing preceded by a peristyle consisting of two rows of columns supporting horseshoe arches. This part of the complex was depicted in 1831 by military painter Alexandre Genêt. Restoration work on it began in 1855: the columns were replaced by plain pillars, and the varied profiles of the capitals were made uniform. The wall tile, which probably already featured geometric patterns, was replaced by wainscoting with white and blue scalloped trim. During the same period, the grand reception hall, behind the peristyle, also underwent renovation aimed at “redecorating the whole complex […] in Moorish style to match the rest of the buildings.” The plans called for a large amount of plaster staff on the upper parts of the walls was, however, simplified. These features repeat the profile of the pillars used in most of the late Ottoman mansions and palaces of the Ottoman Regency of Algiers, ike those of the famed Palace of the Bey in the city of Constantine. Large windows were cut into the walls, topped with an ornate flared arch sometimes called an Algerian arch, glazed with petal-shaped windows. The walls themselves were covered with polychrome ceramic tile featuring plant motifs.

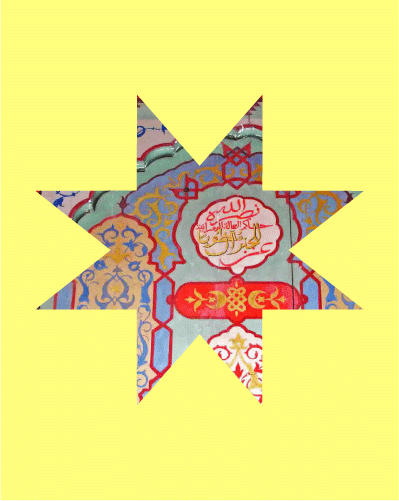

In 1865, for Emperor Napoleon III’s official visit to Oran, the decoration of the upper part of the walls and ceiling was completed, with murals and paintings that matching the organization and motifs of illuminated Korans. These decorations had been presented to the Western public thanks to the books by Owen Jones. The ceiling inscriptions in thuluth script are verses from a poem composed by Muṣtafā b. ʿAbd Allāh Bin Daḥḥū, author of Fatḥ Waḥrān (The Conquest of Oran), to decorate a building erected in Oran by Muḥammad b. ʿUṯmān Bey in 1207 h. /1792-1793. The script imitates the Arab panegyric style but proclaims the glory of the Emperor, as well as that of Governor Randon and General Montauban. It could have been designed by the orientalist Edmond Combarel, who also studied at the École des Beaux-Arts.

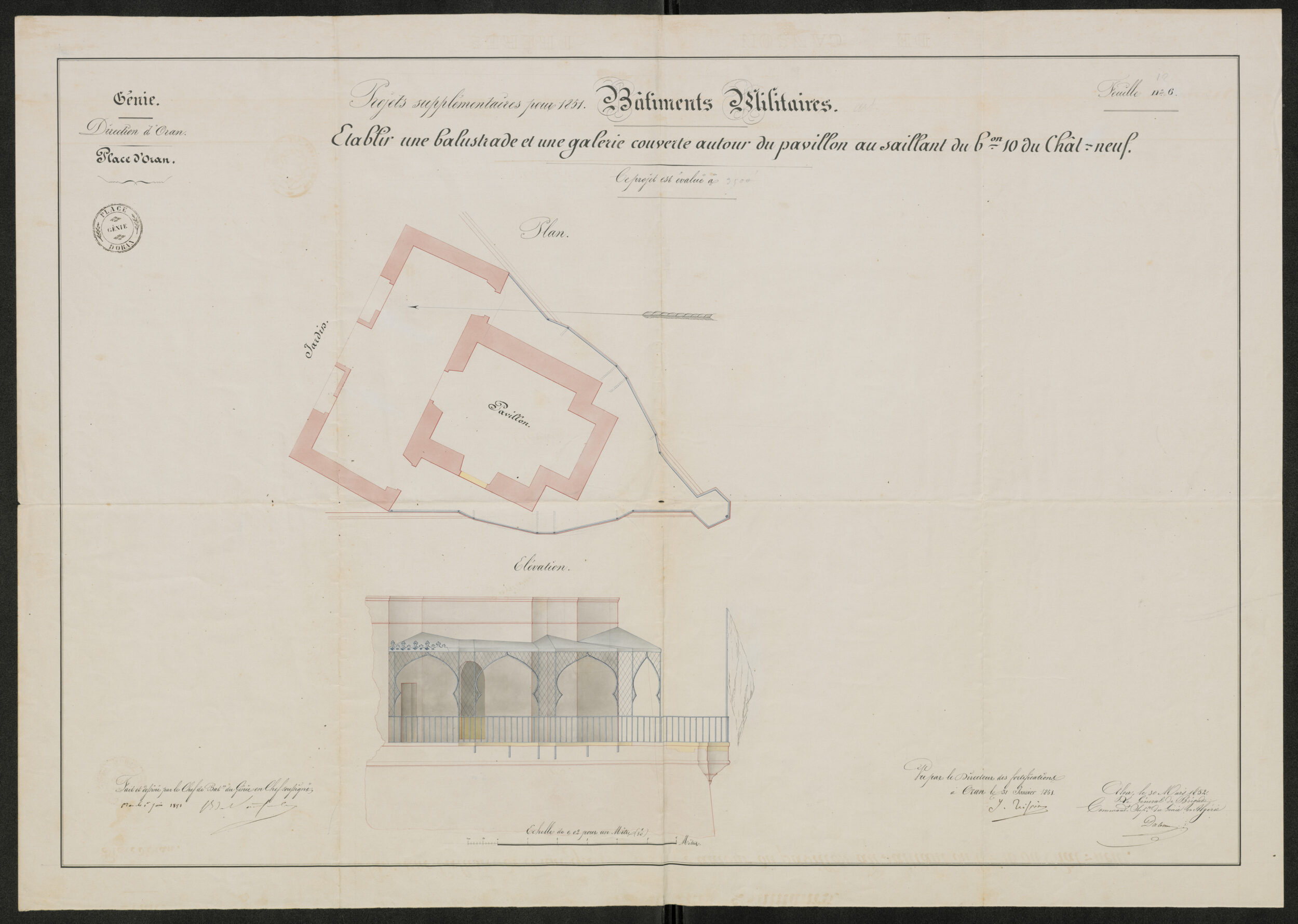

Between the two main buildings, a passageway leads to a small garden in front of a dwelling nested into the peak of the bastion. Now called “le pavillon de la favorite” (“the favorite wife’s villa”; “the smoking room” in the French era), the building features rich interior decoration. In the lower part, painted wooden panels that imitate a polychrome tile facing form a geometric network. The upper parts, like the doors and windows, are decorated with cast plaster panels with scalloped edges or embellished arches filled with patterns of pine cones, palm fronds, or stylizeed leaves. This stucco quotes carved decoration at the Alhambra, and were probably cast from those molds. On the outside, the villa is bordered by an ironwork balustrade dating from 1851. It offers a spectacular view of the old city, spread out at the foot of Mount Murdjadjo.

In 1913, Albert Ballu, the architect in charge of historical monuments in Algeria, filed a request that “the towers, the reception hall, the general’s quarters, and the smoking room in the garden” be placed on the preservation list. He aimed to oppose city government plans to raze the fortress which, at the time, was considered an eyesore: “an annoying screen that cuts off the view from the Place d’Armes and the Promenade de Létang, Oran’s balcony overlooking the sea.” None of these projects were carried out.

In the early 1980s, part of the terrace was cleared of its Ottoman-era and French colonial buildings to make room for an 18-story hotel, which remained unfinished.

The part of the old palace that has been preserved now houses the Algerian national offices for the management and operation of cultural heritage (the OGEBC). Recent archeological explorations have uncovered elements of the earlier, Ottoman-era decoration on the floors, walls, and ceilings. They are quite fragmentary, however, and it would be difficult to restore the entire edifice with them.

Artistic looks

Archaeologists and architects attempts to rediscover the original appearance of the bey’s palace before it was “orientalized” by the French military in the neo-Moorish style from the 1860s onwards using traces of ancient decorations, plans from Spanish archives and drawings from the very beginning of the French occupation.

Edition

Claudine Piaton

3D restitution and production

Archéovision production

Filming

Kouider Metair, Insaf Sersar, Hichem Mechiche, Houari El Kébir

Words of people

About this audio

On a visit to the palace, young people from Oran tell us about their impressions of the Arabic inscriptions in the grand salon dedicated to Napoleon III.

Interviews and writing

Kouider Metaïr, Claudine Piaton

Editing

Éléonore Clovis

Licence

CC-BY-NC-SA